How To Be (sm)ART About Storytelling

Think of your favorite movie. What comes to your mind? The intriguing plot full of twists? The storyteller? The hilarious characters? The tragic scenes? The brewing conflict with the final showdown? Scenes with one-liner dialogue? Or no dialogue? Quotes? Storytelling is a powerful tool to capture people’s attention, connect with their emotions, motivate them to do something. Whether you're sitting around the campfire, watching a movie in a theater, or playing a game on your phone, you've most likely experienced the magic.

Writing, however, is a completely different story. In the year 2000, I wrote my first full-length screenplay. It took three months to write and ten years to forget. After receiving the judge’s feedback from the competition, it was clear that I had to learn a lot more about the craft: "Great start. You sucked me into the story right away. The ending? Never expected, like Sixth Sense. But reading script in-between was such a pain."

And he went on and on for 10 pages about my plot, characters, dialogue, etc. I spent the next six years studying the elements of a good story, and almost ten years writing the second screenplay. My screenplay, Waltzing Kingdoms, was a finalist in an international competition. Those in-between years, I was focusing on the elements that make a good story. While there are hundreds of books on how to write a story, this article focuses on these basic elements from a pragmatic point of view.

12 Lenses

This article helps you take your initial script or scenario you wrote to the next level. You're going to break down a story into 12 elements looking at your piece through 12 lenses. Through each lens and the questions you ask, you can tweak your story. One last note, this article is not going to deal with learning objectives. Writing a story for the sake of ART is different from writing one for learning. That's why we're not just using ART lenses generally but (sm)ART lenses that are more focused on practicality for L&D.

What Are The 12 (sm)ART Lenses?

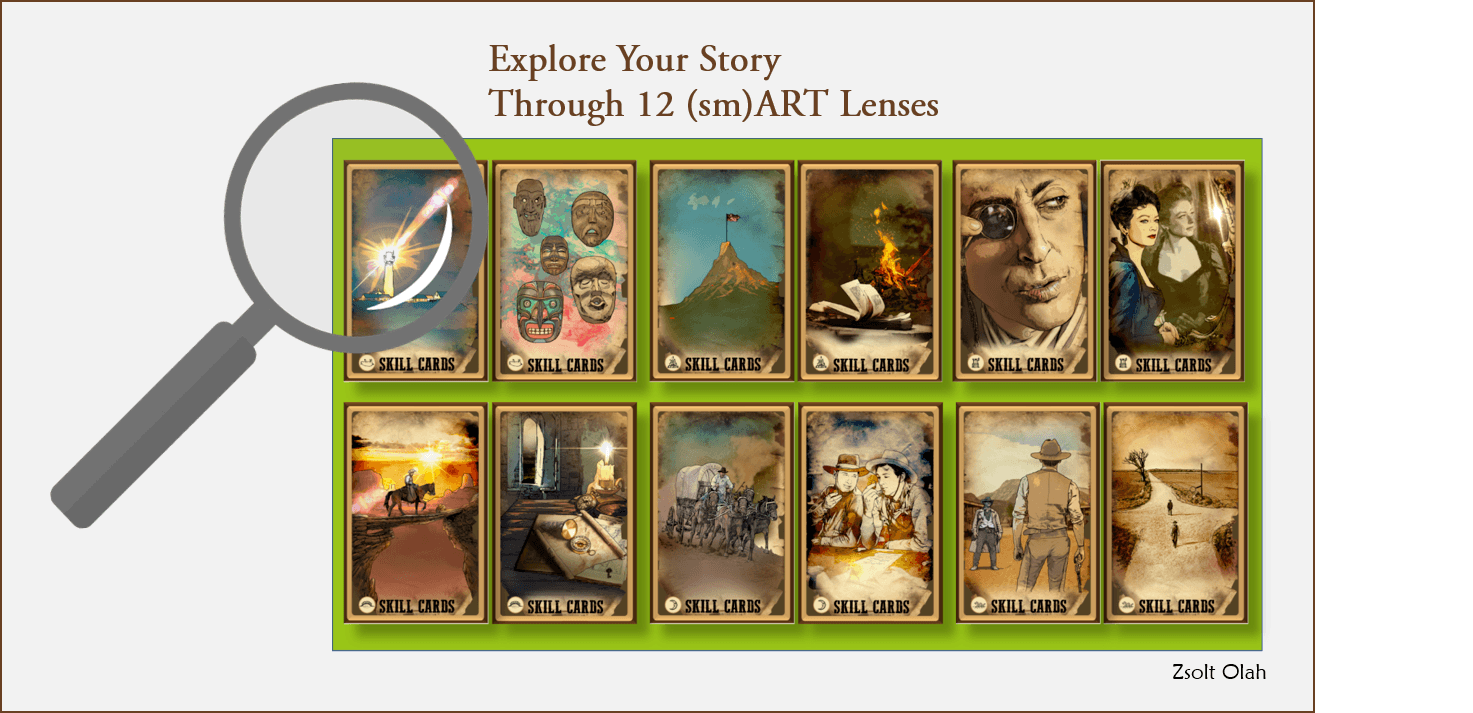

Writing an effective story for learning (whether it is scenario-based learning, short stories, case studies, etc.) is a skill. Therefore, these 12 (sm)ART lenses are collected below in a deck of skill cards:

Depending on your story's goals, structure, duration, and purpose, you may or may not need to spend time on all 12 cards with in-depth exploration. The most complex scenario for L&D is probably live-action shooting in a mini-series where you must be (sm)ART about scenes, locations, budget, dialogue, etc. But what if you just have a text scenario between two workplace characters? You can still use the cards to explore the scene, improve the dialogue, and maybe completely change the point of view...it's up to you how you apply the card deck below.

Lens #1: Theme

The theme is the heart of the story: the emotional connection, the big idea, the purpose. What is the deeper meaning of the story in one word? Examples: love, inclusion, leadership, trust, change, innovation.

(sm)ART Questions To Ask

- What is your theme in one word? This one word or expression is the underlying message for the main learning point.

- How do you start your story? Is your opening scene memorable? Does it emphasize the theme well? Think of non-verbal dialogue, descriptions, settings, locations, genre, etc. For example, if your theme is about burnout and the scenario is a coaching conversation practice, you could emphasize that theme with a screensaver on a computer: a hamster in a wheel.

- Is the theme explicitly defined in the story? Do you spell out the theme or do you just hint? It's not right or wrong, rather two different approaches. A less subtle scenario with an open ending is a great team huddle conversation starter.

Tips:

- You’re creating a story that exposes a message. If the story is merely a placeholder for the message, it can backfire. If the message gets too obvious, you may risk losing the emotional connection.

- You can be creative about how themes are carried over to the workplace. Maybe your character shows up on posters? Mousepads? Intranet pages? Or even in real life during an all-hands meeting as a reminder?

- Can you reuse your digital assets supporting the theme in various other channels for pre- and post communications?

Lens #2: Genre

How would you categorize your story? Think of genre as a combination of story/action, plot, characters, and setting. Examples: drama, comedy, war, thriller, crime, etc. Each of these genres comes with an expected plot, character-types, etc.

(sm)ART Questions To Ask

- Your genre will set the tone of your story. Who’s your target audience? What genre would resonate most with them? What's your realistic budget?

- Who are the stakeholders for the project? Make sure they are on board with the genre and the theme. (HR and Legal can often throw in challenges late in the game if they are not consulted early on. And it can be costly.)

- What else has been done before? Make sure you don’t repeat last year's marketing campaign.

Tips

- Be creative in merging genres to fit both your budget and time. For example, if this is a sci-fi story (setting), you may not want to build out the future of your company for shooting locations. Instead, use two characters returning from the future (plot) and keep the current time and context for the setting. Combining sci-fi and comedy may be an interesting way to tell the story without breaking your budget.

- If you can't think of more than 10 genres, check out Netflix's collection of over 100,000 entries. For instance, “Biographical 20th Century Period Pieces About Fame” is genre 77,456 [1].

- If you’re not doing a live-action movie, rather digital storytelling with animated characters or stock images, you may be able to afford other genre options.

Lens #3: Setting

The setting is about where the overall story takes place regarding time period, location, and social context. The time period can be generic, as in the past, present, or future. Sometimes it is a time period that focuses on a specific year or century. In workplace learning, the most common time period is present, as it can be expensive to alter reality. Location is the specific place in time. The social context is the overall cultural and social environment where the story takes place.

(sm)ART Questions To Ask

- Setting, theme, and genre work together to establish the context of your story and create the overall experience your audience will go through. How do you know what a good setting is?

- The opening scene with the first few seconds in a specific setting should set the tone and the underlying message. To be conservative, you can keep your setting realistic (time: now; place: workplace; social context: going through a change curve with a reorg). However, you can also use the setting to depict the consequences of yesterday's actions (time: pas; place: workplace; social context: decision-making, where someone from today is trying to convince the past to change their mind without revealing the mission).

Tip: When in doubt, keep it simple. Keep in mind that your ultimate goal is learning (or engaging your audience in thinking) and not entertainment.

Lens #4: Scene

From a writing perspective, a scene is a distinct unit with a fixed location and time. If either the location or the time changes, it is a new scene. Every scene is a mini-story with a beginning, middle, and end. From the audience's perspective (in the actual production), a scene serves as the continuum or context holding plot points together that drive the story.

Either case, a scene is one of the most important storytelling elements because it creates a space for your characters, their dialogue, shows the conflict, sets up the plot, etc. All these together create an emotional connection. (Ask people what they remember from movies—scenes are the most common element: the bar scene from Star Wars; "Oh, Captain. My Captain" from Dead Poets Society; "I see dead people" from The Sixth Sense; or, "I’ll have what she’s having…" from When Harry Met Sally.)

(sm)ART Questions To Ask

Could You Come In Later In The Scene?

Remember, you’re not recreating reality, you’re imitating reality. In movies, you never see people circling around in the parking lot trying to find a spot (unless this is part of the plot). Examine every scene. Would the scene make sense if you cut some of the dialogue or action out?

Tip: Entering a scene late not only saves time but creates suspense and engagement.

Could You Leave Earlier From The Scene?

Again, each scene has one goal: to move the story forward. Once that moment happens, you can exit.

Tip: The human brain has the amazing power to fill the narrative gaps as long as the story is consistently told. (And this ability is often “abused” by writers to trick the audience into thinking one way until the twist happens.)

What Is The Local Conflict?

Each scene should have a local conflict brewing. It is like putting logs on the fire. If there is no tension between characters or inside a character (think hearts and minds), the scene can go flat.

What Do Characters Want In The Scene? What Do They Actually Need?

Think of a scene as an independent little story with a beginning, middle, and end. Each character enters the scene wanting something. They might not know what they need, though. Whether the audience is aware of the difference depends on the writer. If your scenario is about safety, don't just describe the situation and ask what the right thing to do is. Paint an authentic scene of what really happens on the job. We often have to choose between priorities and not between right or wrong.

Tip: Note that you don’t need multiple characters and extensive dialogue for a scene to work. In fact, we learn a lot about characters just by watching how they’re doing their everyday thing, and how and when they’re not saying anything. For example, think about the difference between the following two scenes in the exact same manager’s office. Not a word is said in either scene. How would you describe the two managers?

- Scene #1: The manager has gazillion tabs open on the computer, post-it notes all over the desk. He’s on the phone, nodding while texting. Finally, he hangs up and turns to the person sitting across, shaking his head with all the craziness going on.

- Scene #2: The manager has one tab open in a browser as he puts his status on do not disturb. The desk is despicably clean. As the phone rings, he checks it for a second and declines the call. Finally, he turns to the person sitting across showing his gratitude for waiting.

Lens #5: POV

The point of view (POV) is about who is telling the story. This is an important decision that needs to happen early on (or change consistently later). While in movies you may encounter multiple POV approaches, usually in workplace learning we don’t have the time and resources to accommodate the complexity of it. The other difference between movies and learning is that in movies you identify emotionally with a character but do not control it. In most learning experiences, you assume a role to interact with characters. The POV then determines the information available for you to play that role.

There are 2 common ways to tell a story:

1. First person

- Protagonist

- Villain

- Secondary character

- Observer

- Unreliable narrator

2. Third person

- Third person limited

- Third person omniscient

Tip: Note that “person” does not mean a living human. It can be an animal, an object, or even a process. POV strictly tells you who’s telling the story.

(sm)ART Activity To Explore

As the same story can be told from a different point of view, experiment with shifting the narrator:

- Create an index card for major characters, processes, and tools involved in your story. You can do this virtually with collaboration tools such as Mural or Miro.

- In a small group, let everyone pick a random card and give a one-minute elevator speech about what the story would look like being told from that perspective. Virtually, you can let participants write their approach on the card and then vote.

- Don’t just include people in the pool. Does the story revolve around a process? How about telling the story from the process's perspective? Or the final product's perspective? (“How the bill gets made?”)

Tips

- Picking the villain as the point of view can provide you an interesting angle. And that villain can be either a person or something more abstract. For example, I pitched an idea of Pheed once. Pheed is a fictional character representing feedback. What if feedback was a person? How would Pheed look at the world? Giving and receiving Pheed can be an interesting way of looking at how we treat feedback, etc.

- Switching POV is a powerful tool if you have the budget and resources. Imagine you’re building a story that explores human relationships (whether it is sexual harassment, inclusion, power situations, etc.). With the traditional, linear storytelling, you see the events unfold from one character’s point of view. However, what if you could switch the character and see the same event from a different character’s point of view? What if you don’t know who you are? Imagine you’re in a meeting in a Virtual Reality (VR) setting where people react to you, but you are not sure who you are...

- Interactive videos can also be powerful for storytelling when you can switch between POVs. This example shows a linear story about a boy who’s dreaming.

- Anywhere in the video, you can switch between reality and the dream. Today’s technology allows us to create interactive videos within a budget.

Lens #6: Perspective

While POV deals with who’s telling the story, the perspective is about how the storyteller perceives the world. It’s the lens the narrator is wearing to view themselves and the world around them. And as we know, these lenses can distort our vision!

(sm)ART Questions To Ask

How Do I Create Engaging, Yet Authentic Characters?

One of the common mistakes learning professionals make when creating stories is that they’re focusing on the learning objectives first, then the scenarios to teach those objectives, and then finally, the characters who “deliver” that scenario. This can lead to bad dialogue and a lack of authenticity. The problem is that you’re putting words into the mouth of a strawman. Create your characters first; give them a perspective on how they perceive the world and themselves. Then, put them into a scenario where there’s a conflict.

How To Create Perspectives?

A common trick is putting yourself in the shoes of your character and answering these questions with slogans, quotes, lyrics, titles, whatever… just start the creative juices flow.

- How do I see myself?

Internal mirror. The answer describes your internal perception of yourself and determines your feelings and thinking. - How do I see the world?

External window. The answer describes your perception of the external world and determines the interpretation of the events and your reaction to them. - How do I believe the world sees me?

External mirror. The answer describes your belief about the impact you’re making. It determines how you internalize the reactions you experience in the world.

Imagine the same scene with the same character but different perspectives:

Perspective #1:

- How do I see myself?: Fish Out of Water→Why am I here?

- How do I see the world?: Titanic→I know how this ends.

- How do I believe the world sees me?→Ugly Betty→Next, please.

Perspective #2:

- How do I see myself?: “The Dude”→Just chillin’

- How do I see the world?: Honey, I Shrunk the Kids→Me vs. the zoo. Who’s going to win?

- How do I believe the world sees me?: Lion King→We rule.

With these simple three answers, your character's reaction to situations will be consistent. If you watch The Office, a great exercise is to pick some of your favorite characters, answer these three questions based on how they usually react, and then watch the episodes again with this perspective.

Lens #7: Characters

The heart of every story is the character. Characters bring the story alive with their actions (plot), interactions (dialogue, non-verbal communication, conflict, confrontation), and emotions (tone, feelings, reactions). In workplace learning, the user not only identifies with a character but actually plays an active role by making decisions for them.

At a minimum, you need one character, the protagonist. Each character has a perspective (motivation and interpretation of events) and a special relationship with the plot. The plot is what drives the story forward, but it is a character that initiates the plot. A common mistake is to have an outline of what happens in the story (plot), and then add characters to go through the plot points. While the audience will understand what’s happening, they will question why.

(sm)ART Questions To Ask

The main character goes through a “character arc” in the story. If your character does not change by the end, if the character does not learn something that triggers a mindset shift, the story might fall flat.

At the beginning of the story, ask these questions:

- What does your character want?

- What does your character actually need?

- What external obstacles are holding the character back?

- What internal obstacles are holding the character back?

The answers for a, b, c, and d will help you define the following dynamics:

- Character arc: a→b

As your character goes through the story, they will realize what they want is not really what they need. - External conflict: a/b→c

The external conflict is the tension between what the character wants (early on) or needs (later) and the obstacle that stands in the way (often represented by the villain's goals). - Internal conflict: a/b→d

The internal conflict is the tension between the character's wants/needs and the internal flaw the character must conquer in order to reach the external goal.

Tip: Subject Matter Experts may not be good actors. They may need additional time and coaching for acting.

Lens #8: Dialogue

By dialogue, we don't only mean people talking to each other. Dialogue is verbal and non-verbal interaction between two or more characters. Dialogue is where most of the fundamental mistakes happen in writing for learning scenarios.

(sm)ART Challenges With Learning Scripts

Long Sentences With Perfect Grammar

Remember, you’re imitating a real-life interaction. Nobody talks in perfectly orchestrated marketing sentences. There’s no Grammarly in real-time conversations. This may happen because the script is reviewed by SMEs, HR, Legal, and Marketing in the vacuum. They just read what they were given, so naturally, they focus on the text and the message instead of the context.

Characters Do Not React To Each Other; They Say Their Own Lines

In real life, characters often misunderstand each other or ask probing questions. They react non-verbally when they don’t want to say what they think. They don't just wait until the other person stopped talking, etc. Always read out the dialogue live with SMEs.

Does Your Character Say What They Think And Feel?

If your characters say exactly what they think and how they feel, your story will be boring and ridiculous.

Does Your Character Use The Same Tone Talking To All Other Characters?

Do you speak the same language with your lunch buddy as with the CEO? Or with your manager and Legal?

Tips:

- What is not said in a dialogue is as important (if not even more) than what is said

- Use silence like white space on the screen to emphasize the major point.

- Characters holding back information is a powerful tool. Use it in the script, as people do in real life (sometimes on purpose, sometimes not).

- Be creative with how and what the audience knows. Most comedies include storylines where the audience knows more than the character on the screen. (“Don’t go there! How come you can’t see he’s lying?!”)

- How a character says something (or does not say something) is as important as what they say.

- Always read the dialogue out loud

What sounds good in your head is often ridiculous when you say it aloud. This is generally true for any narration or audio script. It sounds way faster in your head than in real life. You will also notice the flow of the language just doesn’t work.

Lens #9: Plot

The plot is a series of events that happen to drive the story in the most effective way. Think of it as the structure, while the story is the building. A common application of the plot structure is Joseph Campbell’s Hero’s Journey. Written for screenplays based on the hero’s journey is Christopher Vogler’s book, The Writer's Journey: Mythic Structure For Writers [2]. The Writer’s Journey is probably more practical for visual storytelling.

(sm)ART Questions To Ask

Can Two Movies Have The Same Plot And Yet Tell Two Different Stories?

Two movies with almost identical plots can be two completely different stories. A good example is Wings of Desire by Wim Wenders and its US remake City of Angels. The plot is almost identical: an angel documenting humans, as complex as they are, falls in love with humanity and gives up eternity for the human experience.

However, Wings of Desire is about humanity, while City of Angels is about Nicholas Cage and Meg Ryan (I like Meg Ryan btw) getting together. There’s even a scene, identical in the two movies, that does not make sense in City of Angels. The plot point is the same, but the story has changed (in the original, every actor speaks their own language, while in the remake everyone speaks English).

Tips

- Study the plot structure of Writer’s Journey (based on Joseph Campbell’s Hero’s Journey*) to understand the flow. However, this is a form not a formula. Don’t take it literally by hanging your story elements on the plots and expect a good story at the end.

-

- The Ordinary World: the hero is seen in their everyday life

- The Call to Adventure: the initiating incident of the story

- Refusal of the Call: the hero experiences some hesitation to answer the call

- Meeting with the Mentor: the hero gains the supplies, knowledge, and confidence needed to commence the adventure

- Crossing the First Threshold: the hero commits wholeheartedly to the adventure

- Tests, Allies, and Enemies: the hero explores the special world, faces trial, and makes friends and enemies

- Approach to the Innermost Cave: the hero nears the center of the story and the special world

- The Ordeal: the hero faces the greatest challenge yet and experiences death and rebirth

- Reward: the hero experiences the consequences of surviving death

- The Road Back: the hero returns to the ordinary world or continues to an ultimate destination

- The Resurrection: the hero experiences a final moment of death and rebirth so they are pure when they reenter the ordinary world

- Return with the Elixir: the hero returns with something to improve the ordinary world

*Strictly following the formula for every story has been facing a lot of criticism. Use it when applicable in your situation. Storytelling is about solving a problem not always a spiritual journey of rebirth.

- Feature screenplays are usually two hours long. You don’t have that time to build out your hero’s journey in detail. However, you can apply the journey to even a simple workplace scenario in a condensed form. A couple of seconds of silence can be an impactful way of depicting the refusal of the call.

Lens #10: Story

The story is the flow of scenes in the timeline with one or multiple plot points. You can have the most sophisticated plot filled with twists and turns, and yet the flattest story ever. The plot is what happens. The story is why we care about the plot. A good story is not just told but shared! So, technically, it’s story sharing. A story comes alive with the help of your audience. And so, you must know your audience.

(sm)ART Questions To Ask

Do You Have At Least The 3 Major Components Of A Good (Learning) Story?

- Relatable characters with unique personalities, goals, and beliefs (aligned with the learning or performance goals). If your audience can't see themselves in the characters, they might not care about the situations, and the story becomes a knowledge test.

- Conflict both internal and external (that exposes the learning or performance goals). Without conflict, there is not change. Without change, there's no drama.

- Authentic situations and challenges where the characters find themselves in a conflict naturally (to provide ample reflection time on how to apply the experience to the workplace). This is the hardest one to pull off. If the situations don't apply to your audience, it doesn't matter how good your story is. Why would this happen? For example, if you need to create an ethics training for everyone, and one of your situations is about accepting gifts, a ticket for a cruise ship around the world might not be the most authentic context for many. (No, I did not make it up.)

Tip

- Stories are engaging because our mind is actively participating in putting together the “puzzle pieces” to see the big picture at the end. If you give away all the pieces, or worse, without even shuffling them, your puzzle is too easy and too boring.

Lens #11: Conflict

Conflict is the tension between two or multiple characters. Think of conflict as a brewing storm with all the signs getting stronger and stronger. Confrontation is the height of the conflict. If you rush into confrontation without building up the tension in a conflict, you risk losing the audience. The most engaging stories build up conflicts both externally (storm coming) and internally (finding the courage to break up an unhealthy relationship before it’s too late).

(sm)ART Questions To Ask

You don’t need to budget for “expensive physical damages” to show brewing conflict and its impact. Silence, non-verbal expressions, and hard decisions we can relate to can be used to build up the tension.

When creating a story for learning, we’re under tremendous time constraints. We don’t have two hours to build out a conflict. Therefore, focus on the main source of conflict, the one with the biggest impact. You may want to think in episodes covering different situations each, rather than a complex movie structure.

Lens #12: Confrontation

It’s showdown time! The brewing conflict leads to the unavoidable event of a confrontation. It is the height of the tension. Conflict is not about two characters pitted against each other. It is about strong wills to achieve their goals. The moment their roads cross is the confrontation. If any of the characters are weak and are willing to step aside, the story is dead. Make sure their integrity is at stake.

(sm)ART Questions To Ask

In Learning and Development, we don’t generally deal with lethal conflicts and confrontations. The tension and consequences are usually more nuanced. Therefore, make sure you build a story around one clear conflict. It can be complex in layers, just as reality is, but break it down to one central problem.

How To Avoid Bad Confrontations?

Make sure the confrontation is not over-hyped with emotions like a bad stock photo. Your scene should be consistent with the theme, genre, and plot points leading to the final countdown. A confrontation without conflict is most likely a bad one. Without brewing conflicts, there's no tension. Without tension, confrontations may seem construed.

How Many Confrontations Do You Have?

Usually, there is one final confrontation right before the resolution. You can be creative using the height of tension to engage the audience:

- What if you stopped the story and asked the audience what happens next?

- What if you built interactivity in the situation with branching?

- What if you “teased” the audience with interim confrontations (when you think the hero is going to do it, but they change their mind at the last moment…)

Confrontations In Live Shooting Mini-Series?

If you’re doing a live shoot, you film scenes by locations, not in chronological order. This is to save time and resources for setting up. Make sure you have a “script supervisor” who notes any potential deviation from the script. The story will be told in chronological order, and slight changes filmed in a different order can throw off the plot when it comes down to the confrontation.

Conclusion

How to use this resource? Decide which skill cards are applicable to your story. Apply the selected skills by exploring your story through the associated (sm) lenses. Play what-if with the cards: collaborate with others by asking the participants to throw in as many what-if scenarios based on the card as they can. Go for quantity, not quality. Then vote for the best alternatives. This is a practical guide on the 12 lenses and the skills they represent. If you want to dive deeper into storytelling for training, I recommend Rance Greene's book, Instructional Story Design [3].

If you want to use the physical deck of these skills cards, feel free to connect with me on LinkedIn.

References:

References:

[1] Complete searchable list of Netflix Genres with links

[2] The Writers Journey: Mythic Structure for Writers

[3] Instructional Story Design