Misperceptions, Misconceptions, And Myths

Are you an expert in learning? Can you evaluate instructional practice? A study involving over 3,000 adult Americans revealed that “everyone is an expert” when it comes to learning.

While people believe that they can identify effective teaching, they actually have limited knowledge of effective teaching practice. In the study, nearly all respondents believed that they were relatively skilled at identifying great teaching strategies, and more than 75% considered themselves above average in evaluating instructional practice [1].

Having gone to school does not make anyone an expert in education. Unfortunately, this over-confidence has serious consequences. The large majority of participants believed in learning myths that do not lead to effective teaching methods

An overwhelming share of the public believes in myths about teaching and learning. Close to 90% of respondents indicated that students should receive information in their own learning style. In this view of learning, an audio learner would receive material in an audio format, while a visual learner would get material in a visual format [1].

While there are excellent articles and books on the subject of learning myths, this article explores the fundamentals of why myths exist, why they don’t ever die, and why it is so hard to change people’s minds about them.

Let’s start with a self-reflection! When was the last time you realized you believed in a myth?

Are any of these statements a myth?

- Brainstorming is more effective as a group activity than asking participants individually to contribute ideas.

- Humans only use 10% of their brains.

- Deaf people can understand most of what others are saying through reading lips.

- People are especially sad on Mondays.

- Highlighting important parts of a text for memorization and rereading the content is one of the most effective learning strategies.

- Eating a lot of turkey makes us tired and sleepy.

- The ability to learn is determined by our intelligence.

- You remember 10% of what you read, 20% of what you hear, 30% of what you see, 50% of what you see and hear, 70% of what you say and write, and 90% of what you do or teach others.

- Red wine is made from grapes.

We’ll get back to these in a little bit! First, let’s clarify the difference between misperceptions, misconceptions, and myths. They are all related to how we see and interpret the world around us.

Mental Models

One of the most important and fundamental elements you must be aware of before discussing misperceptions, misconceptions, and myths are mental models. Mental models are internal representations of the external world that are thought to influence perception and decision-making.

Mental Models As Shortcuts

We humans couldn’t operate in the world without mental models. When you go into a store to buy a new shoe, you have a mental model of what a shoe is. Imagine if you had to inspect every single object thoroughly to decide if it was a shoe or not. We don’t even have to go to the store anymore! We are able to recognize shoes online. We have a mental model, a generalized idea about what makes a shoe a shoe. (If you think it's obvious, read this article [2] about Machine Learning and AI about identifying shoes.) In short, mental models, as shortcuts, provide efficiency in the world.

Mental Models As Navigation Tools

Mental models can also help us navigate the world. For example, before the iPhone appeared, we didn’t really have a mental model of swiping on mobile devices. We used keys and buttons. Blackberry, anyone? When Apple introduced the iPhone in 2007, we built a mental model of how screens work by touching and swiping them. I had several encounters with early kiosks, ATM machines, and other screen devices where I instinctively tried to swipe.

What Can Go Wrong With Mental Models?

While mental models can help us navigate the world, these shortcuts can cause some trouble also. Some common issues with mental models you may encounter:

- Incorrect or wrong mental models

- Outdated mental models

- Mismatched mental models

- Overused mental models

How do you spot a mental model error that might lead to misguided thinking? This article [3] goes into detail with an example of the belief that people behave in strange ways during a full moon.

A complete analysis of more than 30 peer-reviewed studies found no correlation between a full moon and hospital admissions, casino payouts, suicides, traffic accidents, crime rates, and many other common events [3].

At the same time, a study conducted in 2005 still finds that 70% of the nurses still believe there are more patients and chaos during full moon nights. How is this possible? The author then explores a phenomenon called "illusory correlation":

Hundreds of psychology studies have proven that we tend to overestimate the importance of events we can easily recall and underestimate the importance of events we have trouble recalling [3].

Let's take one of the examples from the list you looked at earlier: people are generally sad on Mondays. Apparently, it is a myth.

Why Do We Believe In This Myth?

According to illusory correlations, you remember those Mondays where you were sad while ignoring other Mondays where nothing ordinary happened. You also tend to hang out with others who follow the same mental models, which reinforces your beliefs. You listen to songs about sad Mondays, watch movies, read poems...in other words, you look for and notice everything that supports your beliefs while ignoring everything else that does not. This illusory correlation is then supported by confirmation bias. You see what you want to see.

Confirmation bias is the tendency to search for, interpret, favor, and recall information in a way that confirms or supports one's prior beliefs or values.

Perception And Mental Models

Are you good at drawing? Some people are amazing at drawing life-like sketches. I can't. I didn’t really understand why until I read Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain by Betty Edwards (later, I also learned that the left-brain/right-brain theory is a myth too). I learned that I draw what my mental model of something is rather than what I actually see. When I was supposed to draw a chair, I drew a chair: not the chair that was in front of me but a mental model of a chair I had in mind.

In the book, there was a sketch of some sort I had to reproduce on paper. It wasn’t anything, just lines. I was copying down the sketch on paper when my daughter entered the room. From her angle, the paper was upside down. She said: “Daddy, that’s a great parrot!”

I had no idea what she was talking about. Then I looked at the drawing from her angle, and there it was: my best parrot ever. Today, I know this is a common trick for people learning how to draw. By drawing something upside down, your brain suspends the mental model of whatever you’re supposed to see, and you start observing light and darkness. You don’t draw what you know, you draw what you see.

Inaccurate Mental Models

Misperception is a wrong or incorrect interpretation of the world. It is a version of the world we perceive, interpreted through a lens of distortion. Using the mental model shortcuts, our brain interprets the world around us, so we get what’s important without spending too much conscious effort on figuring out everything. That's good. We can spend time on more valuable efforts. But sometimes, it is not a good "feature" to have.

The other problem with mental models is that they might not be correct in the first place. If you learn something the wrong way, for example, in sports or music, it is much more difficult to adjust later on. Things also evolve in the world, and our mental models may stay out of date.

Mental Model Mismatch

Finally, a common problem with mental models appears when there is a mismatch between reality and the selected mental model. This happens a lot in design. You expect a certain application to work one way, while the designers had a completely different idea. Mental model overuse (a kind of mismatch) happens when you master one mental model and you're trying to force it on every problem you see. For example, you learn about gamification and from then on you're solving every problem through gamification.

Reasoning With People

What do mental models have to do with misconceptions and myths? Our mental models explain how the world works, including learning. Since they are an integral part of how we interpret the world, people may have a strong emotional attachment to them. If the models are incorrect or inaccurate, you can’t just tell people to throw them away! The message may sound like you’re not only addressing something that is incorrect with how they see the world but their own identity. And when you get attacked as a person, you get defensive!

In their mesmerizing book, The Enigma of Reason, authors Hugo Mercier and Dan Sperber explore how we, humans, like to believe that our decision-making process is based on reasoning, yet in reality, it is often illogical [4]. They use several examples of illogical thought processing. In one example, participants were still influenced by a story about a person after they had been told that what they read was utterly fictitious.

Think about that! First, you receive a piece of information as a fact. Then, you’re told that it was made up. Fake news. Ignore it. And still, that known "fake fact" will still have an impact on your thinking and decision-making after. Does this remind you of social media strategies in today’s world?

You're Wrong!

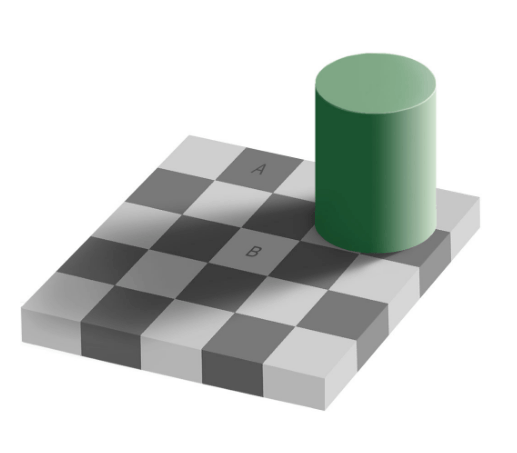

One of the great examples I often use to illustrate how careful we have to be with our own perception of the world is Adelson's checker-shadow. It is discussed in detail in The Enigma of Reason book as well.

Imagine if someone you don’t know (and therefore you may not trust) claims that on the checkboard below, tiles A and B are the same shade of gray.

The picture depicts a checkerboard, with a green cylinder casting a shadow caused by a single light source. Media License: Copyrighted Free Use | Media Source: Copyright: Edward Adelson

There is no way this person is right! You can clearly see that. Tiles A and B are not the same shade of gray! This is a fact. Well, they are the same shade of gray. If you don’t believe it, check it out here. Unless you're trained not to, your brain literally changes what you see.

Why Do We Have This Fault In The Brain?

In The Enigma of Reason, the authors explain that it’s not a fault. It’s by design. Most of the time, we are more interested in the context, the concept that pictures represent, rather than a two-dimensional gray sketch of shades. The meaning, the concept it represents, helps us to interpret the world, make decisions, and communicate with others.

But this “design” comes with challenges. If we have an incorrect mental model, our interpretations of the world, the concepts we understand might not be a true representation of reality. That’s when misconception happens. Note that models are models: our current best understanding of the world. As our knowledge evolves, models evolve. One way to have misconceptions is by sticking to an outdated model. (Some doctors used to believe that smoking expanded the lungs.)

Dealing With Misconceptions

As science educator David Hammer noted, scientific misconceptions possess four major properties:

- Stable, and often strongly held beliefs of the world

- Contradicted by well-established evidence

- Influence how people understand the world

- Must be corrected for people to achieve accurate knowledge

The fourth element is important. We won't be able to change someone's mind about any myth until the underlying misconception, including the strongly held beliefs of the world, is addressed. And it's not just about the amount of data or research findings.

Dealing With Myths

If these statements above are true for misconceptions, what about myths? Are myths different from misconceptions? Misconceptions are a wrong or incorrect interpretation of the world. Often, pointing out the incorrectness or the source of illogical thinking, they can be addressed and corrected.

In some way, they overlap with myths. However, myths have a deeper emotional connection to how we see the world. They are often part of our wishful thinking. Think of myths as misconceptions on steroids that you’re emotionally attached to, or even addicted to!

I'd argue that there's a complex 5th element that myths include beyond the four above for misconception:

- Myths feel right and correct because they do include some half-truth, and they’re often driven by ideology.

- People who believe in learning myths have experienced the “half-truth” part and then generalized from there.

- They built their mental models based on the half-truth part of the myth. Any attack they see on the myth or the ideology behind is a personal attack on their own experiences.

- Everything that fits their vision (through the lens of the mental model) just makes their belief stronger. And everything that doesn’t fit is suspicious or might be an exception.

- Misconceptions can grow into myths and by entering "tribal knowledge," where we don't even question the origin of the truth anymore. [6]

The more they invest (time and emotion) into the belief, the harder it will be to change.

Why Do Myths Never Die?

Forcing people to read a study or shouting at them on social media rarely leads to success. In fact, it may just reinforce their mental model, forcing them to cut ties with people who have a different opinion and returning to the bubble where this myth is still being promoted.

"Yes, I see that evidence but in my opinion..."

"In my opinion..." or "In my experience..." is one of the most common arguments I see on social media defending a learning myth. How can you argue with an opinion? Change can only happen through trust, listening, and conversations by finding a common ground with people. The more you try to take this myth away from a person, the deeper it might get.

It’s like trying to get rid of a ditch with a spade: The way to go is not by digging deeper but by filling the gap. It's about adding, not taking away.

Your Myth Challenge

With all this in mind, take a look at the list of potential misconceptions or myths again and answer the question: which ones do you believe are true? But this time, spend time on each and reflect:

- How do you know if it is a myth or not a myth?

- What evidence do you base your judgment on?

- What mental models do you have on the topic? Where did you get them from? When?

- When was the mental model last updated?

- Have you ever encountered people who believe/don't believe in it? What was their argument?

"Every model is wrong. Some of them are useful." Models evolve over time. Make sure you don't get stuck with an outdated one.

- Brainstorming is more effective as a group activity than asking participants individually to contribute ideas.

- Humans only use 10% of their brains.

- Deaf people can understand most of what others are saying through reading lips.

- People are especially sad on Mondays.

- Highlighting an important part of a text for memorization and rereading the content is one of the most effective learning strategies.

- Eating a lot of turkey makes us tired and sleepy.

- The ability to learn is determined by our intelligence.

- You remember 10% of what you read, 20% of what you hear, 30% of what you see, 50% of what you see and hear, 70% of what you say and write, and 90% of what you do or teach others.

- Red wine is made from grapes.

The answer is all of them. Each of these statements is a myth. While they may seem true, evidence suggests they are not more than wishful thinking. You can find most of them in the book, 50 Great Myths of Popular Psychology: Shattering Widespread Misconceptions about Human Behavior.

Red Wine Example

Let’s look at the red wine example. If you’ve never seen or studied winemaking, your thought process may go like this:

- I know there's red wine, white wine, and rosé.

- Wine is made from grapes.

- Grapes come in different shapes, sizes, and colors.

- Since grapes are pressed to make wine, its juice determines the color of the wine.

- Red grapes have red juice; white grapes have white juice.

- Therefore, red wine is made from red grapes.

There’s some half-truth in this mental model. Yes, we press grapes to make wine, and some grapes are red. But “red grapes” don’t have red juice.

During the production of red wine, on the other hand, the skins remain in contact with the juice as it ferments. This process, known as “maceration,” is responsible for extracting a red wine’s color and flavor [8].

In fact, if you remove the red skin from the fermentation, you can make white wine from red grapes. While you may care about wine, I’m sure your emotional attachment to the color of this drink is less of a factor than to some of the fundamental myths that are out there in the learning space.

Learning Myths

If you noticed, I deliberately avoided learning myths so far in this article while discussing misperceptions, misconceptions, and myths. There is a reason for that. Since you’re reading this article, you are most likely a learning professional passionate about learning. I wanted to make sure you have an open mind about these fundamental concepts in contexts that you might not care about as much as you do about learning.

There are excellent articles, books, blogs, even videos on specific learning myths. The goal of this article was for you to have a better understanding of why people have a hard time changing their minds about believing in learning myths.

Where to start? I suggest reading Clark Quinn's book, Millennials, Goldfish & Other Training Misconceptions: Debunking Learning Myths and Superstitions.

My Two Cents

What are some of the most effective tools and methods to address learning myths? If I had to narrow the list down to two takeaways, I would suggest the following:

- Critical thinking

Practicing critical thinking (thinking about our own thinking) I believe, is one of the most underrated yet extremely powerful tools you can have in your toolkit. - Building your network

In reality, we don’t have time to dig into papers, validate their credibility, interpret the language that is often written for scholars, etc. My advice is to follow the people and organizations that do the research for you and then interpret the results [8].

Conclusion

Whether it is you or someone you know who believes in some of the learning myths, remember the main points when building your strategy for tackling the issue:

- You can’t change anyone’s beliefs. They can change their own.

- Without thinking about the mental model behind a learning myth, it is unlikely that any research and data would suddenly turn someone around. Most likely, what you get is a blindly defensive attitude.

- Misconceptions and myths must be corrected before someone can gain accurate knowledge.

- You're not alone in this fight. Follow people and organizations tackling learning myths.

- Critical thinking is one of the best tools to start with.

References:

[1] What Do People Know About Excellent Teaching and Learning?

[2] Ethics and Moral Code in AI Part 2: The Bias challenge

[3] How to Spot a Common Mental Error That Leads to Misguided Thinking

[4] The Enigma of Reason by Hugo Mercier (Author), Dan Sperber (Author)

[5] 50 Great Myths of Popular Psychology: Shattering Widespread Misconceptions about Human Behavior by Scott O. Lilienfeld (Author), Steven Jay Lynn (Author), John Ruscio (Author), Barry L. Beyerstein (Author)

[6] List of common misconceptions

[7] What's the Difference Between Red and White Wine?

[8] People and organizations to follow:

People:

- Jane Bozarth, Patti Shank, Julie Dirksen, Karl Kapp (on games and gamification)