Discussing Training Worthy Of Attention

Look at the faces of people in most in-person training sessions and you’ll see some people nodding off, daydreaming, or otherwise not engaged. People don’t come to workplace training with a need to be “filled up” with content. If they are there willingly, they have specific goals they want to achieve (such as more organized and valuable meetings or using the new tool for data analysis). If they are there unwillingly, they have many pressing things to think about or work on during what they see as enforced captivity. Technology-based learning often suffers from even less engagement, as it is easier to multitask, which effectively means low or no attention.

Some think that delaying the next button so people must spend a certain amount of time on each page pushes people to engage more. People in forced captivity training situations may be unhappy. We learn less when unhappy or anxious.

In the last two articles, I have discussed attention and its impact on learning. The first article debunked the commonly-held-but-wrong notion that our attention span is decreasing because of technology. The so-called research doesn’t exist. Neuroscientists say our mental processes have not changed much in hundreds or thousands of years. My last article discussed how incredibly complex attention is and how that complexity affects learning.

In the workplace, we should assume that people have too many things to attend to; because they do. But how do we design in this situation? How do we create training worthy of attention?

One unconventional starting approach would be to figure out which training is worthy of attention and which isn’t. Training that is worthy of participant’s attention is important, prevents poor personal and organizational consequences, or helps people gain needed skills. Checkbox training (where what is really needed is to tick a box that says you have been “trained”) should be straightforward and easy to complete. We can then spend the greater time building training worthy of attention. The rest of the article assumes that training is valuable and needed.

First, Gain Attention

Robert Gagné, a well-known American educational psychologist who worked with the Army Air Corps training pilots, is one of the pioneers of using learning sciences and psychological sciences to improve outcomes from Instructional Design and instruction. He tells us that because participant’s attention can be (and often is) elsewhere during instruction, we must gain attention before we do anything else. Marketing practitioners know how to capture attention so we can borrow from their playbook. Known ways to gain attention include:

- Something unexpected.

- Anything that stirs curiosity.

- A compelling image, video, or sound.

- An interesting story, question, or fact.

- A relevant scenario.

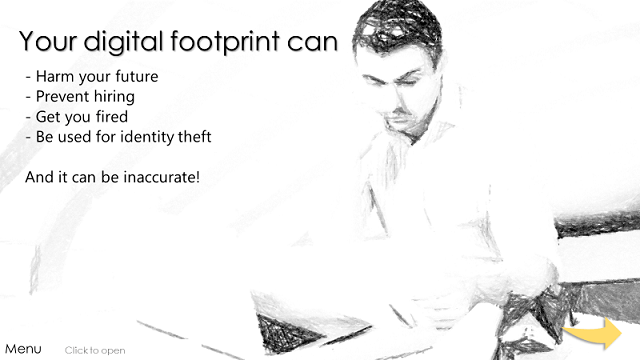

For example, an eLearning course on online privacy presents dire facts and a scenario to help participants focus (attend to) prevent unwanted problems.

Figure 1. Example of course pages designed to gain attention. (Source: Make It Learnable series)

Are People Paying Attention?

But what about keeping attention?

It’s hard to know how big a problem attention is during instruction. Attention is difficult to measure, according to Szpunar and fellow researchers. We can measure attention indirectly, by watching what people are doing (such as taking notes, responding, and so forth). And we can measure it directly by asking people at intervals if they are paying attention (which becomes a distraction and disturbs attention). Both methods are obviously problematic because they may not be accurate at all.

Here’s what we think we know about attention during learning activities. Attention varies and it appears to get harder to pay attention over time. Many Learning and Development (L&D) practitioners think this means we should make instruction extremely short. But an extremely short training intervention, especially if it is new knowledge, can leave out context and make it hard to see the big picture and how to apply what is presented. For example, for a three to four-minute video on chemical safety, it might be very hard to include enough context so people know how it applies in their situation.

Another idea for making it easier to pay attention is making learning fun. If you’ve ever watched an exceptionally engaging commercial but could not remember what the commercial was plugging, you have experienced the problem of fun details taking over primary purpose. There’s too much fun but not impactful training. A colleague recently told me how she attended a truly engaging workshop for female entrepreneurs. But afterwards, she realized that she didn’t learn anything she could use. So, engagement doesn’t necessarily mean learning.

Encoding And Retrieval

Because it’s hard to measure attention, let’s switch to the outcomes of attention that are most critical for organizational learning. We know that without attention, we likely have no learning. So light attention may yield some learning but there’s the possibility of increased misunderstandings from not being able to tie concepts together. We know lack of transfer (of knowledge and skills from instruction to the job) are commonplace. So even if we have attention, people may learn but not be able to apply (especially since we too often provide little or no realistic practice). And lastly, we know that information and skills not used on the job are quickly forgotten. Research shows that this type of forgetting is a common occurrence.

We know that attention is fragile so continual attention is unlikely. So, when a trainer or instructional designer says “I taught that so they should know it”, they may not realize how memory works. We need to design knowing that attention is a problem, even when people are focused on what we teach or design.

I’ll discuss designing for transfer in the future, but for now, let’s consider how we help people focus and remember. The process of getting information into long-term memory that is then usable for job performance is complex. There are 2 processes that help us understand how this occurs.

1. Encoding

If we want or need to remember what we are learning, our mind must make information storable in Long-Term Memory (LTM). We call this process encoding. There are 3 main ways we encode information:

- Visually, as images.

- Auditorily, as sounds.

- Semantically, as meaning.

The most common encoding method is semantic, which has a lot of implications for remembering (retrieval).We store information not so much like a recording but with context. For example, when you store information about what happened during a specific holiday, you are likely to also store how you felt and good or bad things that occurred. This is one of the reasons why certain songs bring back very specific memories.

2. Retrieval

We “remember” by retrieving it from storage. Information stored in LTM is most easily retrieved by meaning or association. As a result, not making instruction personally meaningful (relevant) to the audience is likely to result in far less learning and storage. And if we can help people associate concepts that go together, they will be more likely associated in LTM.

There are some well-known reasons why information in LTM may be hard or impossible to retrieve. The two types of forgetting issues that happen the most in LTM are interference and lack of consolidation.

Interference means that we forget because memories interfere with each other. Interference can happen when prior knowledge interferes with what we are learning or when what we are learning interferes with prior knowledge. Interference occurs most often when prior knowledge and what we are currently learning are similar. And interference may be one of the causes of the difficulty in fixing misunderstandings (previously learned but inaccurate information).

Lack of consolidation(consolidation is when neurons are altered to form memories) happens when information does not get encoded. This can happen because the move from STM to LTM wasn’t successful. Or because there are problems withneurological processes that encode information. Some scientists say consolidation takes time and if interfered with, may not happen.There are other reasons for forgetting or not encoding but these two are the most common for retrieval from LTM.

Have you ever tried to remember something someone told you (say, a book you should read) by saying it over and over in your mind? If so, you were using auditory encoding. The most common way that information in long-term (storage) memory is encoded, we believe, is by meaning (semantic encoding). Meaning is therefore critical for long-term memory and it’s why generic bits of training aren’t easy to remember.

Encoding and retrieval have important implications for designing learning. I’ll list them today, and next month I’ll discuss them in more detail.

- Relevancy.

We should make content and activities as relevant as possible to audience needs.People aren’t there to remember generic content. They are trying tofit information with what they know and use it to meet their needs. - Retrieval cues.

When we encode information in LTM, we also store context information. Retrieval cues tell us that to make information easier to retrieve, we should train and practice in ways that are like how information will be used on the job. One example: If people need to look up certain information in a database on the job, have them look up that information in that database while training. - Chunking.

Break content up into smaller, but still cohesive units that include the job context (to make retrieval easier). Chunks should be smaller for people who know less about the topic. But they should never be so small that they leave out context. - Prior knowledge.

Help people tie new information to prior knowledge to make understanding, encoding, and retrieval easier. Make sure their understanding is accurate so they can build accurate schema (organization of topics) in LTM. - Spaced learning.

Rather than provide critical information once, help people more deeply encode information by having them process information multiple times. (Marketing uses this a lot!) - Low stakes quizzes and questions.

Build in ongoing retrieval activities (such as quizzes and questions) to practice retrieval. Ongoing retrieval activities make retrieval more durable.

All of these approaches work well together to make it easier to learn (encode) and use (retrieve). Next month, I’ll discuss the 6 methods that improve encoding and retrieval. If you want me to cover specific aspects, leave me a message.

References:

- Bor, D. (2012). The Ravenous Brain: How the New Science of Consciousness Explains Our Insatiable Search for Meaning. New York: Basic Books.

- Caple, C. (1997). The Effects of Spaced Practice and Spaced Review on Recall and Retention Using Computer Assisted Instruction. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences & Engineering, 57, 6603.

- Dempster, F.N. (1988). The Spacing Effect - A Case Study in the Failure to Apply the Results of Psychological Research . American Psychologist. 43 (8): 627–634.

- Gagne, R. (1985). The Conditions of Learning (4th.). New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

- Gagne, R.M., Wager, W.W., Golas, K.C., and Keller, J.M. (2004). Principles of Instructional Design, 5th Edition.

- Lambert, C. (2009). Learning by Degrees. Harvard Magazine.

- McLeod, S. A. (2007). Stages of Memory - Encoding Storage and Retrieval. SimplyPsychology.

- Roediger, H. L.&; Butler, A. C. (2011). The critical role of retrieval practice in long-term retention. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 15 (1): 20–27.

- Szpunar,K.K., Moulton, S.T. & Schacter, D.L. (2013). Mind wandering and education: from the classroom to online learning. Frontiers in Psychology.

- Whitten, W.B., Bjork, R.A. (1977). Learning from tests: Effects of spacing. Journal of Verbal Learning & Verbal Behavior. 16: 465–478.