Design Thinking For Instructional Design: Ideation

In the parts one and two of my articles on design thinking for Instructional Design have provided readers with an explanation of why I believe Instructional Designers must adopt a designer’s mindset, an overview of what design thinking is, and where you can incorporate the design thinking process “modes” into your existing Instructional Design process. Now, it’s time to examine how – how to put the methods of design thinking to use in your organization.

Design thinking modes are the mental states that a design team enters into. Instead of being a phase-gate approach, where one phase starts and another state ends, the “process” of design thinking is fluid. But, like a body of water, there is typically a starting point and an ending point. How you get to the final destination make be a unique path based on your circumstances. The design thinking modes are Empathize, Define, Ideate, Prototype and Test. Within each mode of design thinking are methods, or tools, to help the design team achieve the goal of the mode.

In this article and the following one, we’ll focus our attention on the modes I have seen Instructional Designers struggle the most with: Ideation and Prototype. However, just because we are not diving deep into all the modes does not make them any less important or valuable. I strongly encourage additional exploration on how to accomplish the goals of each of these modes. The community of design thinkers are fantastic at sharing their methods, best practices, tips, techniques, and stories. Two of my favorite are the d.School at Stanford and IDEO, but a simple search for design thinking methods will provide you with ample sources of content.

I chose to focus on Ideate and Prototype because in my years of partnering with, leading, and talking to hundreds (if not thousands) of Instructional Designers, I find these are the two modes we struggle with the most. Empathizing with learners, defining the problem (though this is often a tough one, too) and testing align nicely to existing steps in a traditional Instructional Design processes. There are different techniques and the goal is slightly different than in your traditional process, but it still fits well. Ideate and brainstorm, however, are more difficult to fit into a traditional process, require creativity, vulnerability and have strong chance for failure – all of which are uncomfortable for most people, but certainly for Instructional Designers.

Ideation Mode

After you have utilized methods to achieve true empathy with your learners and have clearly defined the problem that needs solving, you will take your observations and understanding of the user audience and brainstorm, or ideate, potential solutions for their problem.

One challenge many Instructional Designers have with the mode of Ideate is the name. First, “ideate” is a word that is unfamiliar to most individuals within an organization. So, we tend to refer to it by its better known relative, brainstorming, which is problematic. As you are likely aware, brainstorming has a pretty bad reputation. Searches on the internet for brainstorming provide not only best practices and techniques, but also a plethora of parody videos, comics, articles and research describing the huge amount of time, energy, money and effort wasted in ineffective, unproductive brainstorming sessions. Therefore, many people from whom you need stakeholder buy-in, will immediately have a negative reaction to any discussion of conducting one (or more) of these sessions.

My advice to you –and it's not rocket science– change the name. You can still accomplish the goals you set out, use the techniques described here, and have a productive session if you call it something else. What that other word is will be up to you. Think about something that your organization could get behind. Is it an “instructional product design meeting”? Maybe it’s a “training innovation session”? Find the right title that matches your culture and move forward. Design thinking is not about following a strict set of rules (including names), it’s about achieving the goal of creating a solution that meets the need of the consumer.

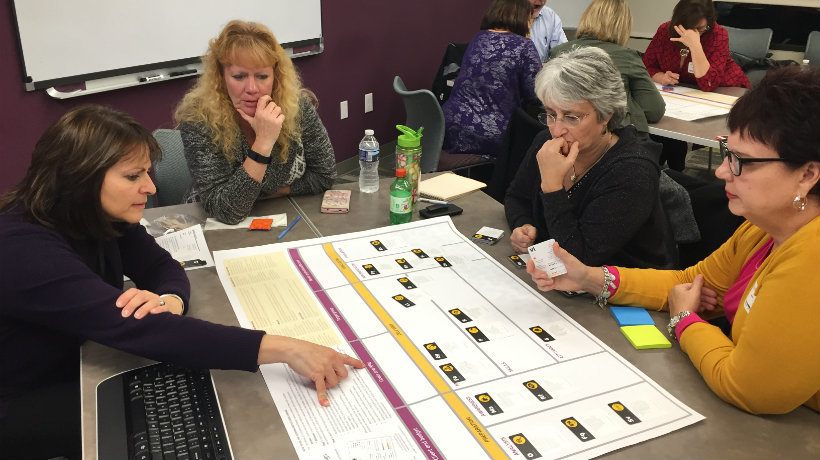

Who you invite to the session, whatever it is called, is key. Having a diverse set of individuals helps to avoid “group think” and falling back on what has been done in the past. Below, are my suggestions of the types of individuals to include in the ideation mode session.

Representative Learners

While not the actual learners who will use the instructional product you design, these are individuals who have empathy for the end user. You include representatives of the learners to avoid the following statement, “That’s what they told you in training, let me show you how it’s really done.”

Leader Of The Learner

Unlike traditional consumer product design, in organizational learning there is another individual for whom you are designing – the leader of the learner. You include leaders to avoid this dreaded version of the same statement from above, “That’s what they told you in training, let me tell you how I want it done.”

Subject Matter Enthusiast

Too often a Subject Matter Expert is asked to join in the design of an instructional solution to ensure the content is accurate. This is a good idea, as we don’t want incorrect information provided to our learners, however it often creates issues. First, experts are in demand and, therefore, often have schedules that are really tight. Getting time on their calendar is difficult, and once there, they are often distracted. Second, experts struggle to remember what it was like to not be an expert. They are “unconsciously competent” where our learners are often “unconsciously incompetent.” Subject Matter Enthusiasts, on the other hand, are those who have a strong understanding of the content and are people who the experts trust. But, they are not as in demand, or as far removed from what it was like to not know, to be a valuable, productive member of the design team.

Project Stakeholder

Again, because you are working to develop a product within the organization, you’ll need to have stakeholder buy in. Getting their input on the design from the start creates a sense of ownership over the design and can address the pushback, which is typically experienced later in the process, immediately.

Instructional Designer

The Instructional Designer should lead and facilitate the session, but not feel as if they are the one who needs to come up with all the design ideas – as they may have in the past. The Instructional Designer will help moderate the conversation, keep the meeting moving, organize the day, and take the ideas generated to the prototype mode.

Once you have assembled the team – and this is where a typical brainstorming session goes wrong – it's really important to structure the session and have a plan for next steps. First, establish and communicate the ground rules, which may include deferring judgement, valuing quantity over quality, ensuring everyone’s opinion is equal, and staying focused on the problem you’re there to solve. Have a loose agenda for the activities you want to run through, and propose times for each activity. After each activity, vote on ideas generated to determine which ones you want to move to prototype. Since the conversation sometimes wanders to other topics during these sessions, it's a good idea to have a dedicated parking lot for things that you can’t solve in this session, but which need to be addressed.

Methods Used

In terms of the activities you facilitate, here are some methods you can use to help generate ideas.

Method 1: How Might We?

Instead of starting with the statement, “We need to design a [insert solution – ILT course, job aid, eLearning, etc.]…” begin the conversation with the performance problem you are trying solve. You should have already created a problem statement during the define mode. Work from that. For example, if your problem statement is, “Employees need to use the appropriate Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) for the job they are doing,” your How Might We questions could be: “How might we motivate our employees to use the appropriate PPE?” or “How might we make wearing appropriate PPE meaningful to our employees?” Reframing the view from starting with the solution to starting with the problem helps avoid constraint inherent in the modality of delivery.

Method 2: Magic Wand

With the method of Magic Wand, you remove all constraints of budget, time, space, etc. The question is easy to ask, “If you could do anything about Insert Problem Here, what would you do?” As a consultant, I used this technique often. One example I remember well was for a company with a problem of employees not having empathy for their peers who worked in the warehouses. They wanted to create training to provide a sense of awareness about the distribution center to the entire organization, globally. When asked, “If you had a magic wand, what would you do?” they responded, "send all employees around the globe to the US to take a tour of the distribution center. At the warehouse, they could meet the employees and get an understanding of the challenges they face each day, to hear and experience what it was like inside the hot, noisy, busy warehouse, and to come up with ideas of how they might change their own work in order to make the lives easier for their fellow employees."

Obviously, sending all employees to a distribution center in the US was not in the budget! So, we designed a virtual tour of the warehouse and had the learners participate in interactions which replicated the work the distribution center employees did. We included sounds and sights, through video and audio, which demonstrated the environment of a large warehouse. By eliminating all constraints, you are only bound by your imagination.

Method 3: Forced Constraints

Forced constraints, which contradicts the above reasons I gave for using the Magic Wand method, is, strangely enough, another way to spark ideas. In Forced Constraints you ask “If you could only do one thing” or “If you only had X time or Y budget”, what would you do? By forcing constraints, you often come down to the heart of the most important thing you want to accomplish. This allows you to focus on one thing instead of being distracted by all that you could potentially do.

Final Word

Whatever methods you choose to incorporate into your ideation or “design session”, be sure to enforce the ground rules, set time constraints on the activities, and vote on ideas that should move to the next mode, prototype. One of the reasons why brainstorming has a bad reputation within organizations is the ideas generated in the session often fail to move from concept to execution. That’s why the next mode, prototype, must quickly follow ideation. It’s also why the last entry in this four part series on design thinking for Instructional Design focuses on prototyping.