How Can We Help People Learn?

Tamaya is working on this week’s medical terminology but nothing is sticking. The television in the family room is loud and so are the arguments between her two daughters. She wonders if Kelly finished her homework because she’s not always truthful when it comes to schoolwork. Joey, her husband, has been working nights and it’s hard to handle everything with him away at night. Tamaya’s job has required adding new skills and now involves even more medical terminology. She simply has no time during her chaotic and busy days to focus on learning this memorization-heavy aspect of her job. If she is going to keep up, she needs to learn it when she has time to concentrate. The training department has provided online medical terminology training for people in her and other job classifications. Here’s a question: Is it our job to help people learn? Or rather help people keep learning? The world of work now involves learning new things all the time and that makes most work harder than it used to be. Can we make that easier? Should we? I say yes to both questions and will explain why.

Before We Can Learn

What we do is not as much about content. It’s more about people.

When listening to learning peeps talk about building learning stuff, we inevitably hear more about the stuff than the people. Might we also consider why we do what we do? Figure 1 is a slide from recent presentations and it suggests what we really develop… People.

Figure 1. Slide from Patti’s Make Instruction (More) Learnable materials

I used Tamaya’s story to make a point. Learning as adults can be difficult as we have complex lives. The degree to which we can keep up in our field (or desired field) is the degree to which we can make a living and keep our lives together. If you and I aren’t their champions and aren’t designing learning in a way that takes this into consideration, we may be making their lives harder.

Can I tell you a secret? I have a chronic illness that has long threatened to derail my career. This is my problem, but without a few people along the way who could help (but didn’t have to) you wouldn’t be reading these words. One is a young woman who has been my guardian angel. She isn’t a VIP and she didn’t even know me, but she reached out. Never forget that helping people with their livelihoods is not impersonal. It truly changes the course of lives.

I’m surely not alone. Many of us have difficulties in our lives. One of the reasons for getting to know about the people who use what you build (in addition to needing to understand what they need) is to put faces and stories to what you do. It will change what you do for the better.

Design In Accordance With How The Mind Works

Back to the science. There are clear, but not always simple, ways to make instruction less hard for people who use what you and I do. Not easy. Easier. Yes, it is true that the world of work has gotten more difficult, and it looks like this trend will continue and even accelerate. It’s our job to help people learn.

The world is already throwing content at workers at a rate never seen before. I’ve been discussing the disruptive changes (unprecedented and displacing existing ways of doing things) to the workplace in the ATD Senior Learning blog and the existing and coming changes to the workplace and our own jobs are overwhelming. I’ve listed those articles in References and I think you’ll find what is happening compelling.

Regardless of the number of disruptive changes coming our way, human cognition is the same. Cognition is the process of gaining knowledge through thinking, experience, and our senses. As a learning sciences advocate, I know that simply throwing content at people is a recipe for overload. I’d like to explain some of the cognitive issues that we need to work around and give you clear tactics that make it easier for workers to learn in these chaotic circumstances. I believe this is one of the greatest problems that Learning and Development needs to focus on in these times.

So in the next few articles, I’ll discuss what cognitive academics tell us about how our minds work and what it means for designing adult instruction and related interventions.

Human Cognitive Architecture

I want to start with what Dr. Sweller calls human cognitive architecture, or how we integrate, process, and use knowledge. If we don’t understand how this all works, we may be making learning harder, by mistake.

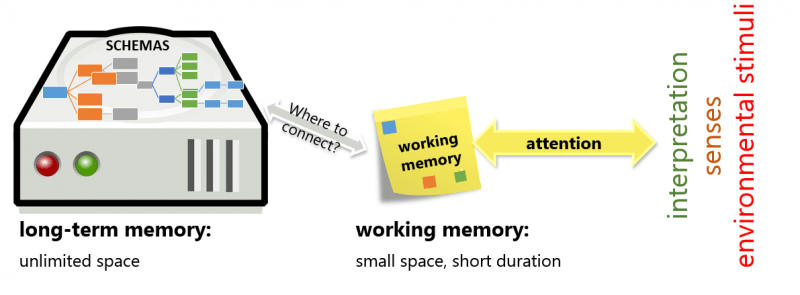

Dr. Sweller is an educational psychologist who has written a considerable number of important works (alone and with other important thinkers), primarily on memory and other cognitive factors and implications for designing instruction. He begins by telling us that the extent to which instruction is effective depends heavily on whether it takes the characteristics of human cognition into account. Table 1 explains primary components of human cognitive architecture.

| COMPONENT | DESCRIPTION |

| Short-term memory (STM) | Short-term memory is a cognitive function with very limited capacity. It is responsible for temporary information holding. |

| Working memory (WM) | Working memory (WM) is a cognitive function with very limited capacity responsible for processing and manipulating information. WM is often used synonymously with STM, but STM holds information while WM is involved in processing it. They are actually believed to be separate systems.

Working memory is complex. It has separate systems that process visual (images) and auditory information. Building instruction that uses WM well is a foundational instructional design task because if it isn’t used well, it is harder to learn. |

| Long-term memory (LTM) | Long-term memory (LTM) is a cognitive function responsible for ultimate memory storage, with theoretically unlimited capacity and indefinite storage and retrieval.

Getting information into LTM and ready for use on-the-job is another critical instructional design task. |

| Schema | We believe that information held in LTM are in schema, meaningfully organized units. These schemas help people with more prior knowledge handle work and problems better.

So one important purpose of organizational instruction is to help people with less knowledge create schema similar to those with more expertise. |

Table 1. Components in human cognitive architecture

How this all works together is rather complicated. I want to simplify it so Figure 1. shows some of the process. In the future I’ll discuss more of what is happening. For now, I simply want you to notice that before you can learn, content needs to make it past attention and working memory. Both are unlikely. So unless we design for human cognitive architecture, we are likely not getting through.

Figure 1. The long and winding road of learning (Source: P. Shank (2016). Making Instruction Learnable)

Because of our human cognitive architecture, learning is necessarily slow. People must build up the schema over time and everything must go through working memory, which is slow and can only handle a little bit at a time.

When a person doesn’t have relevant schema for incoming information, they need to process everything One. Piece. At. A. Time. Working memory makes this a very slow process. When someone has more expertise and understands what is being presented to them, they are able to process elements in chunks of information. They can take in more and faster.

Schemata (schemas) are organized meaningfully, are added to and reorganized as one learns, and they become far more specific as a person gains expertise. Schemas can be embedded in other schemas (so use of headings schema might be embedded in a MS Word schema, for example). My schemas for how to use gluten free flours are embedded in my baking schemas.

Surely you have had the experience of dealing with information you don’t understand. Do you remember having the information go by and understanding little while others nodded their head and asked questions you didn’t even comprehend? Others had schema for that information and you didn’t. Now consider the people you are developing instruction for feeling the same. We are developing people, not content.

Implication: Help Working Memory

The primary implication of human cognitive architecture for instruction, says Sweller, is we must design to not exceed cognitive load. This is mainly because working memory handles processing of content while learning and it gets overloaded easily. Cognitive load means exactly what it sounds like. The mind gets overloaded and cannot think or learn or cannot do it effectively.

Next month I’ll discuss 9 design propositions that Sweller discusses that help people learn (especially people who are new to a topic) with less load. All have been thoroughly researched. Some are easier to adopt than others, but together, they form a system of instructional design recommendations that we can use to adapt our instruction to how people can learn.

References:

- Anderson, R. C., Spiro, R. J., & Anderson, M.C. (1978). Schemata as scaffolding for the representation of information in connected discourse. American Educational Research Journal, 15 (3), 433-440.

- Shank, P. (March 30, 2016) 2025: How Will We Work? How Will Your Job Change? ATD Senior Leaders & Executives Blog.

- Shank, P. (August 25, 2016) The Future Is Now: Transformation of Work and Skills ATD Senior Leaders & Executives Blog.

- Sweller, J. (2008). Human Cognitive Architecture (PDF). In J. M. Spector, M. D. Merrill, J. V. Merrienboer, & M.P. Driscoll (Eds.), Handbook of Research on Educational Communications and Technology 3rd ed., 369-381. New York, NY: Taylor & Francis Group.