An LMS and BYOD Changed A School

The Southport School is a P-12 (K-12) private Anglican school for boys located in Southport on Queensland’s Gold Coast. Established in 1901, the school caters to both boarding and day students and has an excellent reputation for sports and leadership. Historically, the academic strength of the school has been built on the excellence of its teachers, mainly operating in the traditional “chalk and talk” or teacher-led mode. The parents show great confidence in the ability of these teachers to provide a sound traditional education.

A staff survey (Appendix 1) taken in February 2013 showed that more than one quarter of staff had 25 years’ service or more while around 55% had 10 or more years of service.

The question for my colleague Jo Inglis, Head of Learning & Teaching was “Was it possible to make changes to classroom pedagogy in educational technology?” These changes, it was hoped, would lead to more effective classroom practice via increased student autonomy and the focus shifting from product (for example Queensland OP examination results) to process – from lower order Bloom’s skills to Higher Order ones. In Queensland these types of process skills are tested by another set of examinations held in Year 12 – the QCS tests and the students had not performed quite as well as expected in these tests.

The LMS

We felt that the use of a Learning or Course Management System (or equally well, cloud applications such as Google Apps) could be a strong factor in assisting this change.

This approach is commonly referred to as blended learning and is ideally managed as teacher-led and student-centred.

It has been possible, from about 1990 through to 2010, to improve outcomes in the classroom by making traditional teacher-centred pedagogy more efficient using technology. An example might be writing – clearly many students prefer the efficiencies associated with word processors, as do teachers. However, this does not bring about significant change in pedagogy.

By contrast, having teachers use a forum in Moodle (or via other web technologies) has the potential to dramatically change the classroom as my colleague, Dr Jill Margerison discovered.

Within a Grade 8 English class, by having boys write their homework into a forum she was able to leverage the social aspects of learning. Boys helped, responded and even coached other boys. This process needed frequent and timely intervention but, on the other hand there was no tedious marking of individual homework. The advantage of this from the learner’s point of view is that this two-way traffic of work between teacher and themselves is replaced by a multi-way exchanges from which they can learn.

Clearly the teacher role is different and this is likely to cause problems in schools where the use of social learning via the web is seen as an add-on to the teacher’s existing tasks. The school administration will need to recognize the changes this type of practice brings and act accordingly.

Having known quite a few school administrations, I believe this may be the most difficult area of change to bring about.

Why BYOD?

Let’s first clear up some terms. Some people (mostly software vendors) have begun jumping on the BYOD bandwagon by proclaiming a one-to-one program – in which the school obliges parents to provide their hardware as BYOD with mandated device. I’m not buying this for a second as BYOD.

The essential problem that BYOD or properly run 1 to 1 programs solve is that of access. Once every student has a device they have access to the LMS and myriad other web-based services.

However, in contrast to 1 to 1 programs, with BYOD the teacher is faced with a range of hardware, operating systems and applications. Often teachers see this as a barrier initially – “how will I teach them PowerPoint?” they ask.

Of course, it is not a subject teacher’s (or anyone else’s in my opinion) to teach students application specific skills. People learn those skills when they need them. The claim is often made that businesses need school-leavers with these specific skills. However, surely a student who can pick up a new application quickly is a more useful employee.

During three years at The Southport School in Queensland, Australia, my colleagues and I managed to produce significant changes in classroom practice via the use of Moodle and the staged introduction of mobile devices to the classroom.

At The Southport School the BYOD program was introduced in stages, thanks to grants by the Australian Government to all schools for the purchase of devices.

This funding provided the initial impetus for trials at class then year then multi-year levels. Boys in years and classes not in the trials were actively encouraged to bring mobile devices into the classroom.

BYOD and LMS together

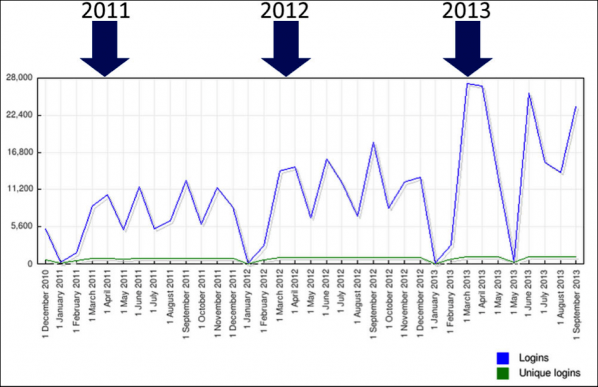

The result of improving access to the Moodle LMS was plain to see:

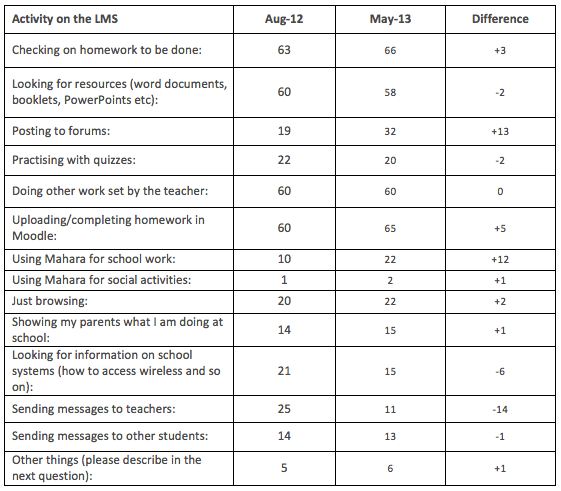

The 2013 figure shows an 83% increase in logons to Moodle.It is interesting to know if there were any significant changes in the way the LMS was being used by students:

The significant increases are in posting to forums and the use of Mahara (an ePortfolio system installed with Moodle).In this particular school environment, students largely chose to bring a device of their own, rather than one of the school supplied devices. A survey in May 2013 indicated that just over 90% of students preferred to bring their own device rather than take one from the school. The survey further indicated that most students had 2 or more devices with them in school. Mostly these additional devices were smartphones such as the iPhone (35%) or an Android phone (10%).Of the school devices that were taken just 3 (2%) were the iPad 1 and 9 (7%) were the Dell Netbooks funded under DER.

How did Teaching Change?

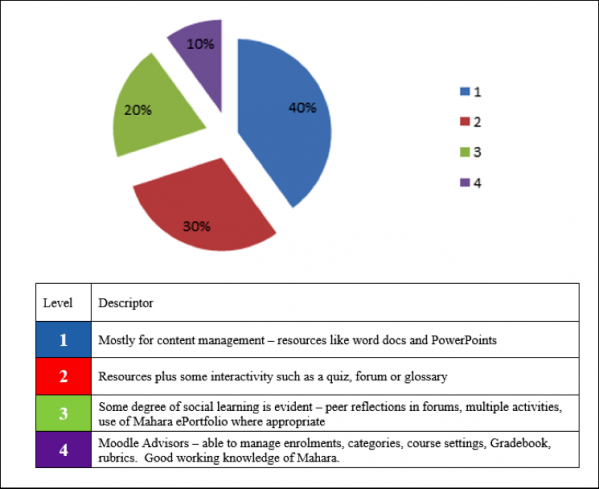

At the start of the year, an audit of staff use of the LMS was also undertaken. This was based around 18 competencies that had been identified as being important by representatives of each school department.By May 2013 30% of the Senior Staff had been audited with the following results:

Percentage of audited teachers working at levels (defined below):

Even such a simple change as learning content being made available via the web can result in significant changes in learning. It is pleasing to note that the majority of teachers (just) were actually moving in more interesting directions through the use of activities and social interaction.

How did the students see it?

From the students’ point of view, we have extensive evidence, via interview, that students find using technology a motivator:

“A lot of the boys in the class feel more comfortable on their computers and learning on their computers than textbook”.

“We’re doing more in Subject Y, like more assignments and stuff”

“Do you find that better than what you were doing before?”

“Yeah, because there’s more stuff to do”

And also that it promotes autonomous use:

“Well in Term 4 we’ve been using Moodle by ourselves … [it’s easier than] having Mr X show us everything on the board”.

“You have the opportunity to do it your own way instead of doing it the way everyone else is”

At the time of writing, late 2013, the school feels it has reached a point where a full-time eLearning Specialist is no longer needed and there is sufficient capability in-house to continue progress.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to acknowledge the help and cooperation of the staff of The Southport School in making this book possible. Many of the staff have given and continue to give their time voluntarily and willingly to help implement Moodle and Mahara at the school. Their enthusiasm and energy in support of boy’s education is truly remarkable.

The author is grateful to the Headmaster of The Southport School, Mr Greg Wain, for permission to use collected data and screenshots from the school’s management system Learning@TSS.

Richard would particularly like to mention the support and leadership of Ms Jo Inglis and the enthusiasm of Dr Jill Margerison.

At the same time it should be noted that any error or advice, which is contained in these pages, is solely the responsibility of the author.

Some of the data presented here were collected as part of successive projects were supported by grants from the Australian Government Quality Teacher Program (AGQTP) and overseen by Independent Schools Queensland (ISQ). The Mahara ePortfolio (2010), the investigation of different types of professional learning (2011) and the eLearning leaders (2012). Thanks are also due to Mr Ian Quartermaine for his supervision of these projects.