Instructional Design Methods To Optimize Time And Learning Efficiency

Stakeholders who request workplace training and other performance interventions often push for speed over quality. Workers are busy and time to learn is time where people could be accomplishing job tasks. We design primarily for speed as a result. Some of the most important learning tactics, such as adequate and varied practice and practice for remembering, are often left out.

For example, sales training for new mobile phones may include phone specifications, images, and diagrams. Designing training for speed too often doesn’t include practice needed for performance. For example, practice over time remembering key specifications helps people use the specifications on the job. Varied practice helping customers select from the newer models for their needs helps people use the specifications in helping people select the right phone. Research shows these types of practice are among key tactics for making training stick and useable.

Speed is a key part of efficiency. Efficiency is the time, effort, and other resources it takes to do something. Efficiency, however, isn’t an adequate outcome unless it also achieves the needed outcomes.

For example, interior painting is far more efficient without covering or moving furniture, removing or taping around light switches and lighting, or taping edges. But not doing these things means likely damage to household items and sloppy work. In other words, efficiencies can compromise effectiveness. Effectiveness is about obtaining needed outcomes.

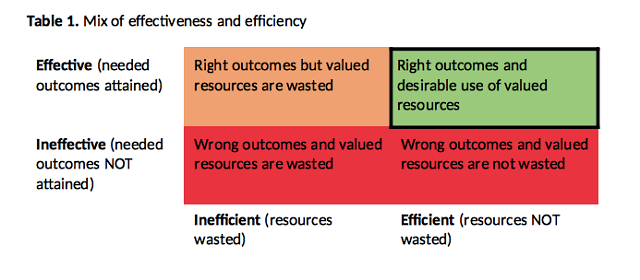

Table 1 shows four mixes of effectiveness and efficiency. The best result is the green area: effectiveness and efficiency are both achieved. The orange area at least gets needed outcomes, but often at too high a cost. The red areas are both bad results. Both offer the wrong outcomes.

Table 1. Mix of effectiveness and efficiency

Getting to the top right box with learning and performance interventions —achieving the right outcomes while not wasting valuable resources—is critical. Efficiency without effectiveness simply gets us to the wrong place faster.

Shortcuts To Learning

According to Cook, Levinson, and Garside in their recent (2010) meta-analysis of research showing the role of time in learning, there are few shortcuts to learning. The greatest effectiveness comes from proven (evidence-based) instructional methods (I write about these a lot on eLearning Industry so check out my other articles). These instructional tactics typically (but not always) add time to learning but we need the time and tactics to produce needed results.

In the rest of this article, I’ll discuss what their meta-analysis tells us about getting needed results efficiently. I’ll explain their insights about whether technology-based instructional methods generally save time over non-technology-based instructional methods. Then I’ll discuss their analysis of specific instructional tactics and their effect on effectiveness and efficiency. Lastly, I’ll pull this all together with a few thoughts on what it means for you and me.

A meta-analysis is a statistical approach that allows researchers to combine results from many studies. Cook, Levinson, and Garside primarily analyzed studies of education and training for health professionals, students, and trainees. I think their results are generalizable to many of today’s workplace learning needs because their audience has many similarities (adults, work setting, need to gain, maintain, and change skills) to the audiences you and I design for.

Q1: Does Technology-Based Instruction Reduce Learning Time?

Many of us have heard that technology-based instruction reduces learning time. When Cook, Levinson, and Garside reviewed studies for their analysis, they found a lot of time variation in time. For example, Spikard found technology-based learning takes a slightly shorter amount of time than non-technology-based instruction. But Dennis found technology-based-instruction takes longer than non-technology-based instruction. It is not possible to make general statements about technology-based instruction being more efficient, because research shows technology-based instruction takes somewhat less time, the same time, or more time than non-technology-based instruction.

This directly contradicts a 1986 analysis of research on adult learners by Kulik and others showing time savings for technology-based instruction over classroom-based instruction. Why is it different? One educated guess is that we much more varied technology-based instruction now. Amount of time is likely driven by factors other than medium. Some knowledge and skills simply take more time to learn.

Research supports the notion that more effective instruction requires certain tactics and takes more time (I’ll discuss some of these in the next section). In my Practice and Feedback for Deeper Learning book, research shows that certain kinds of practice and feedback are much more valuable (effective) than others. We expect these tactics to add time to learning.

Q2: Which Instructional Methods Are Worth The Increased Time?

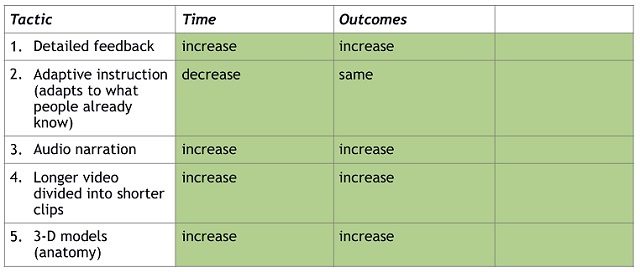

The authors reviewed the research literature to analyze time and results from using more effective training tactics. Four of the tactics (1, 3, 4, and 5) produced increased outcomes but they also took more time. One tactic (2), used less time but had the same training outcomes.

Interestingly, for those who have read my previous article on what research tells us about microlearning, dividing longer video into shorter clips (4) increases overall time spent. Revisiting a subject many times can help people process the same and related content more deeply.

The Bottom Line

Here’s what this meta-analysis says to me. Valuable training outcomes (effectiveness: recall, ability to use what was learned on the job) typically take more time than simple content. The next question, of course, is it worth the time? The simple answer is that we typically don’t get the most valued outcomes from content dumps that don’t include the right tactics.

The discussion section of the meta-analysis says:

… (O)ur data suggest that there are few shortcuts to learning. …

(N)early all modifications… to improve learning outcomes… require more time…

I will explore this more in future articles. If you have specific questions, add a comment so I know what you most want to know.

References:

- Cook, D. A. (2005). The research we still are not doing: An agenda for the study of computer-based learning. Academic Medicine, 80, 541–548.

- Cook, D. A., Beckman, T. J., Thomas, K. G., & Thompson, W. G. (2008a). Adapting Web-based instruction to residents’ knowledge improves learning efficiency: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 23, 985–990.

- Cook, D. A., Levinson, A. J, & Garside, S. (2010). Time and learning efficiency in Internet-based learning: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Advances in Health Science Education, 15, 755-770.

- Dennis, J. K. (2003). Problem-based learning in online vs. face-to-face environments. Education for Health, 16(2), 198–209.

- Kopp, V., Stark, R., & Fischer, M. R. (2008). Fostering diagnostic knowledge through computer-supported, case-based worked examples: Effects of erroneous examples and feedback. Medical Education, 42, 823–829.

- Kulik, C.-L. C., Kulik, J. A., & Shwalb, B. J. (1986). The effectiveness of computer-based adult education: A meta-analysis. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 2, 235–252.

- Shank, P. (2017). Practice and Feedback for Deeper Learning.

- Spickard, A. III., Smithers, J., Cordray, D., Gigante, J., & Wofford, J. L. (2004). A randomised trial of an online lecture with and without audio. Medical Education, 38, 787–790.

- Schittek Janda, M., Tani Botticelli, A., Mattheos, N., Nebel, D., Wagner, A., Nattestad, A., et al. (2005). Computer-mediated instructional video: A randomised controlled trial comparing a sequential and a segmented instructional video in surgical hand wash. European Journal of Dental Education, 9(2), 53–58.