How Important Is Text In An Online World?

Text.

No, not the verb. The noun. And no, not as in SMS, but as in a book, as in reading, as in eLearning.

Text is the vanilla ice cream of eLearning content. Dull and bland. Actually, I am being too charitable. In the online learning world, it’s the unwanted houseguest who never leaves. eLearning designers make all sorts of efforts to avoid using text. (Here is my attempt to transfer 12 pages of text into a 3-minute animation so my online learners would actually learn the content!). It's boring. It's flat. It's not interactive. We don't even skim it—we jet ski over it (Carr, 2011). We don’t even read well online. In a 21st century world, text is soooo 18th century. So why even bother with it?

All (arguably) true. But there are 3 reasons why text matters in online learning. First, most of the world’s accumulated and archived knowledge—its poetry, stories, history, and discoveries—are in text format. Next, in most of the online courses across the globe, text is the dominant form of knowledge transfer. Finally, don’t we need employees, students, teachers, and citizens who are as critically literate and fluent in consuming and producing text as they are in consuming and producing other media?

Houston, We Have A Problem

We’re not getting away from text any time soon, but we do have a problem with text, and particularly text on screens. This article argues that yes, we certainly must design for the online medium—knowledge, and experiences that capitalize on the visual and interactive nature of online learning. But part of that design must include text. We need to both incorporate and modify text for online consumption. At the same time, we must encourage and support our online learners to be able to critically consume and analyze text-based information that is complex and even (horrors!) long.

Reading From Screens: We All Get An F

There are a number of issues with text. First, as a vehicle for helping individuals learn skills or complex ideas, text is often limited. It appeals primarily to logic and is bounded by the meanings assigned to words, often limiting the impression one wishes to convey. Further, text can be inefficient: the recipient of text-based information must simultaneously receive and “translate” text into mental images in order to better comprehend and mentally “envision” the information being relayed. For certain learners, this processing challenge is often a formidable one, and the inability to decode and comprehend text (i.e., reading) often spells failure, for both adolescent and adult learners in formal education settings (Burns & Martinez, 2002, pp. 1-2).

Next, those of us who read online do it poorly. The culprit here is “cognitive load” (the cognitive processing demands placed on a person). Reading from a computer screen increases our cognitive load because we have to scroll, find out where we were in the text, etc. and all of this clogs our mental bandwidth making reading from a screen exhausting and resulting in less capacity to remember information.

Consequently, when reading online, we tend to spend less time on a web page, hyperlink to new sites or pages without returning to the original content, and in an effort to absorb as quickly as possible large amounts of text, we tend to read in an “F” pattern (that is, those of us who read languages from left-to-right). “Eye tracking” research notes that when we read online, we begin by reading the first couple of lines of text in their entirety. However, our eyes quickly move down the left-hand part of the screen using the first word of each line as shorthand to inform us about the remaining information in that sentence. We may, mid-way down the page, read across another line of text, though usually not in its entirety before we again continue with eye movement down the left-hand side of the screen (Nielsen & Pernice, 2010, cited in Burns, 2011, p. 144).

This results in a third, more serious issue—the alteration in the process of reading itself. Rather than employing “deep reading" processes (Wolf, 2018)—focused, sustained attention to and immersion in the text—online readers spend more time utilizing shallow reading techniques. Shallow reading involves browsing and scanning, keyword spotting, non‐linear reading, and reading more selectively, and far less time on sustained attention, in‐depth reading, concentrated reading, and active reading, such as revisiting parts of the text, highlighting and annotating (Liu, 2005) despite the availability of such digital tools. The problem is that we have transferred these shallow online reading techniques to offline reading.

Taken together, these 3 issues—the inefficiencies of text, how we read online, and the deleterious impact of online reading on reading in general—have serious “downstream effects” (Wolf, 2018)—the inability to comprehend text, to critically analyze text and read long pieces of complex text (Wolf, 2018).

No wonder then that so many of our online learners (in my case, adult educators) tell us that they “don’t read” or that they “don’t like to read” and often skip online readings altogether. On a personal note, as someone who loves words and language, I find this to be one of the most tragic consequences of the Digital Age.

Reading From Screens: Lightening The Load

Text will always, I hope, be part of online courses. In fact, it needs to be. A failure to include online text and readings deprives our learners of access to all sorts of knowledge and removes them from the mental conversation with the author that occurs when one is engaged in the reading process. Educated people should be able to consume and produce text. And even more practically, text-based content is cheaper to produce and works better in the low-bandwidth environments, which is the technical reality for so many of the world’s online learners.

In my own experience, I have found in terms of online course design and delivery, that there are ways to improve the above text-related issues (though not necessarily solve them). I offer a few of design and instruction tips here.

Pay Attention To Writing

First, we have to choose our knowledge formats carefully and use these formats for what they are good for—video for demonstration and text for descriptive information and for conceptual knowledge. But it goes beyond mere formats; we have to pay attention to good writing. One of the downsides of not reading a lot is that we see fewer examples of good writing. I’ve found that my own reluctant online readers are more likely to read text that engages them, that uses interesting language and imagery, and that uses stories to explain ideas and concepts. Good writing attracts readers, so heeding the advice of one of the greats (Emily Dickinson)—we should polish our words until “they shine”.

Make It Accessible

The average American adult reads between a 7th- and 9th-grade level. Additionally, our online learners may be wrestling, for the first time, with academic or technical content. Therefore, it’s important to make writing clear, concise, straightforward and idiom-free. In my own work with non-native English-speakers, I often struggle in all of these areas (though there is some debate about the degree to which we should make language simple or complex for English as a Second Language Learner). Generally, I have found the Flesch-Kincaid Readability Tool which analyzes the “grade level” of text to be very helpful. You can also activate this tool in MS Word.

Pay Attention To How We Organize Text

In an online environment, we often have to organize text differently for our learners. This is where research on eye-tracking, and available eye-tracking tools, are of great value as they can help online course designers understand which layouts and placement of text are best for reading online. Organizing text into bullet points, chunking text, highlighting important text with different colors and font styles (but not font size), and using headers, all help to make reading more accessible and serve as effective visual mnemonics (Viau, 1998; Lane, n.d. cited in Burns, 2011, p. 143).

Use Images And Visuals To Highlight The Most Important Concepts

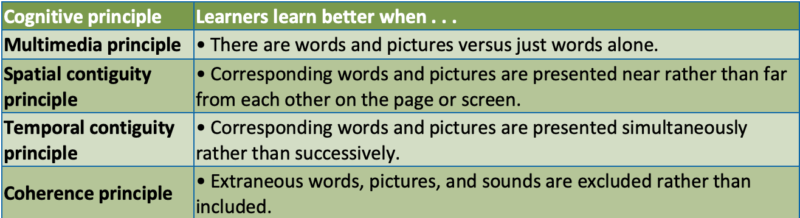

Research on cognitive theory shows that multimedia, that is images, audio, and multimediα may help all individuals, both students and teachers, learn more effectively and meaningfully. For example, narrating a reading via audio (something I often do for non-native English speakers) can assist readers greatly since it activates both aural and visual processing. This “dual coding” potentially results in greater long-term retention of information (Mayer, 2001).

In studying the use of rich media as a teaching and learning tool, Mayer (2001) suggests a number of principles that help to aid working memory and enhance reading comprehension. These principles are outlined in Table 1.

Make It Interactive And Active

Google Docs, Chrome Extensions like Kami, Hypothesis and other online sites like PRISM can make reading active and interactive, making it possible for online learners take notes on what they’ve read and had discussions around these notes.

Active reading techniques are especially important when we want learners to interact with complex or long pieces of text. Three active reading techniques I’ve used are the SQ3R method (Scan, Question, Read, Review and Recall) developed by Francis P. Robinson, an American educator, in 1946. I’ve also put together a "cheat-sheet" presentation about it. A second technique is "text protocols" where learners come together to read and discuss a text using a set of instructions and questions to guide their reading of that text. Finally, I often use Bloom's Taxonomy as a guide to help learners think about how to approach the text and what to look for as they read.

Make It Accountable

If our learners know that they are not being held accountable to do the readings, they won’t. So, as retrograde as this makes me, I always include quizzes on readings and make sure that in discussions, learners must demonstrate that they have read content and have considered key ideas as part of their ideas sharing. In the past, I’ve also assigned learners randomly to summarize (via text or audio) readings. Summarizing is an important higher-level skill and is a great way to see how well learners understood the main ideas of reading.

Take It Offline

The research is clear—we read better from paper than from a screen (Tufte, 1990; Liu, 2005; Carr, 2011; Wolf, 2018). Research strongly suggests that students who read text on print are “superior in their comprehension to screen-reading peers, particularly in their ability to sequence detail and reconstruct the plot in chronological order” (Wolf, 2018). In part this is because paper is easier to navigate, it's tactile (an important part of reading), and it provides us with spatial-temporal markers while we read. Touching paper and turning pages, and especially writing (versus typing) notes aids memory, making it easier to remember what we read and where in the text we read it (Mangen, Walgermo & Brønnick, 2013). So, given this, perhaps we should distribute readings as text or insist that our learners print out the most important readings and read from the printed version?

Conclusion

We need to make text more resonant for screen-based learning but we must not shy away from using text in online courses. Our online learners need to be able to read, comprehend, analyze and evaluate the utility, veracity, and accuracy of the text, in whatever content area they are studying online. As online instructors, we may find we have to help in this task.

Whether for compliance training, continuing education credit or a formal course of study, every profession wants and needs active learners, productive workers and moral, responsible citizens who are critical consumers of text-based information. Rather than eliminating text in our online courses and limiting access to rich and complex readings, we need to embrace text, design for it and help learners hone their online and offline reading skills.

References:

Burns, M. (2011). Distance education for teacher training: Modes, models and methods. Retrieved from http://go.edc.org/07xd

Burns, M. (2006, February). A thousand words: Improving teachers’ visual literacy skills. Multimedia Schools, 13 (1), 16-20.

Burns, M. & Martinez, D. (2002). The People’s Choice: Digital Imagery and the Art of Persuasion. Austin, TX: SEDL.

Carr, N. (2011). The Shallows: What the Internet Is Doing to Our Brains. New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc.

Liu, Z. (2005). Reading behavior in the digital environment: Changes in reading behavior over the past ten years. In Journal of Documentation, 61 (6) pp. 700-712. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1108/00220410510632040

Mangen, A, Walgermo, B R and Brønnick, K (2013). Reading linear texts on paper versus computer screen: Effects on reading comprehension. International Journal of Educational Research, 58: 61–68, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2012.12.002

Mayer, R. (2001). Multimedia Learning. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Tufte, E. (1990). Envisioning Information. Cheshire, CT: Graphics Press.

Wolf, M. (2018, August 25). Skim reading is the new normal. The effect on society is profound. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://bit.ly/2BMd3Bb