How To Blend Asynchronous + Synchronous

This series on selecting and using digital technologies was researched and written initially to help people scrambling to begin using online instruction. But something interesting happened as the articles came out. I started getting tweets and emails from people who had been using online learning for a while. They told me that the articles were helping them thoughtfully select when and how to use asynchronous (on demand) and synchronous (live) learning. Although blending (for learning) often refers to mixing digital with in-person learning, the blend I’m speaking of is blending asynchronous and synchronous digital learning. Research by Kim, Bonk, Tend, Zeng, and Oh, and Lupsheyuk and Adams shows how difficult it is to blend. That’s because there are many choices of what to blend and that makes the task seem quite complex.

Figuring out the best ways to blend is critical because asynchronous and synchronous learning offer different benefits and we want the benefits of both whenever possible. Sitzmann and fellow researchers help us understand that better satisfaction and outcomes with blending are precisely because of merging the convenience and flexibility of asynchronous with the immediacy and social interaction from synchronous. Blending asynchronous and synchronous allows us to gain unique benefits from each modality while overcoming the unique limitations. This is a big deal.

Because learning practitioners often don’t know what different tools are best for, most pick a single tool (most often, virtual classroom) and force fit instruction into that tool. This often doesn’t work well, just as a single type of sports equipment doesn’t work for other sports or a single baking pan doesn’t support different baking needs. Research offers us extremely helpful insights on picking tools to support a wide range of instructional activities. I discussed how asynchronous and synchronous learning supports different types of learning in Part 2. And went into more detail about using asynchronous and synchronous learning in Part 3 (asynchronous) and Part 4 (synchronous).

Advantages And Limitations Of Asynchronous And Synchronous Learning

Hrastinski, Kask, Offir, and others analyze the advantages and limitations of asynchronous and synchronous learning in their research. I merged what I consider to be critical insights into the table below (adapted and condensed from a similar table in Part 2).

| Asynchronous (on demand) | Synchronous (live) | |

| Advantages |

|

|

| Limitations |

|

|

(Primary advantages and limitations of asynchronous and synchronous learning)

Because of these advantages and limitations, research points to the value of using asynchronous elements for content interactions and the value of synchronous elements for social interactions.

An online portable ladder safety course, for example, might include the following asynchronous content interaction elements:

- Videos: Ladder Accidents; Selecting the Right Ladder for The Job; Using the Three Types of Portable Ladders; What Would You Do?

- Ladder safety checklist

- Scenario questions

And synchronous sessions might add:

- Case study activities

- Discussions

- Review questions

By combining asynchronous and synchronous, we can gain the advantages of each while reducing the limitations of each. For example:

- The isolation of asynchronous learning can be reduced by learning with and from others in synchronous learning.

- The flexibility gained through asynchronous elements helps remedy the inflexibility of live synchronous learning.

- The inherent time limitations of synchronous learning can be overcome by adding asynchronous learning, which allows time for deeper processing.

- Asynchronous elements often feel less urgent because they are available anytime. By adding synchronous activities that call upon learning from asynchronous elements, asynchronous elements feel more urgent.

The ability to get the benefits of asynchronous and synchronous is a big, big deal, as all the advantages are valuable to learning. Research shows that selecting a good blend is challenging, but once we understand what each modality is best for, this becomes far easier to do.

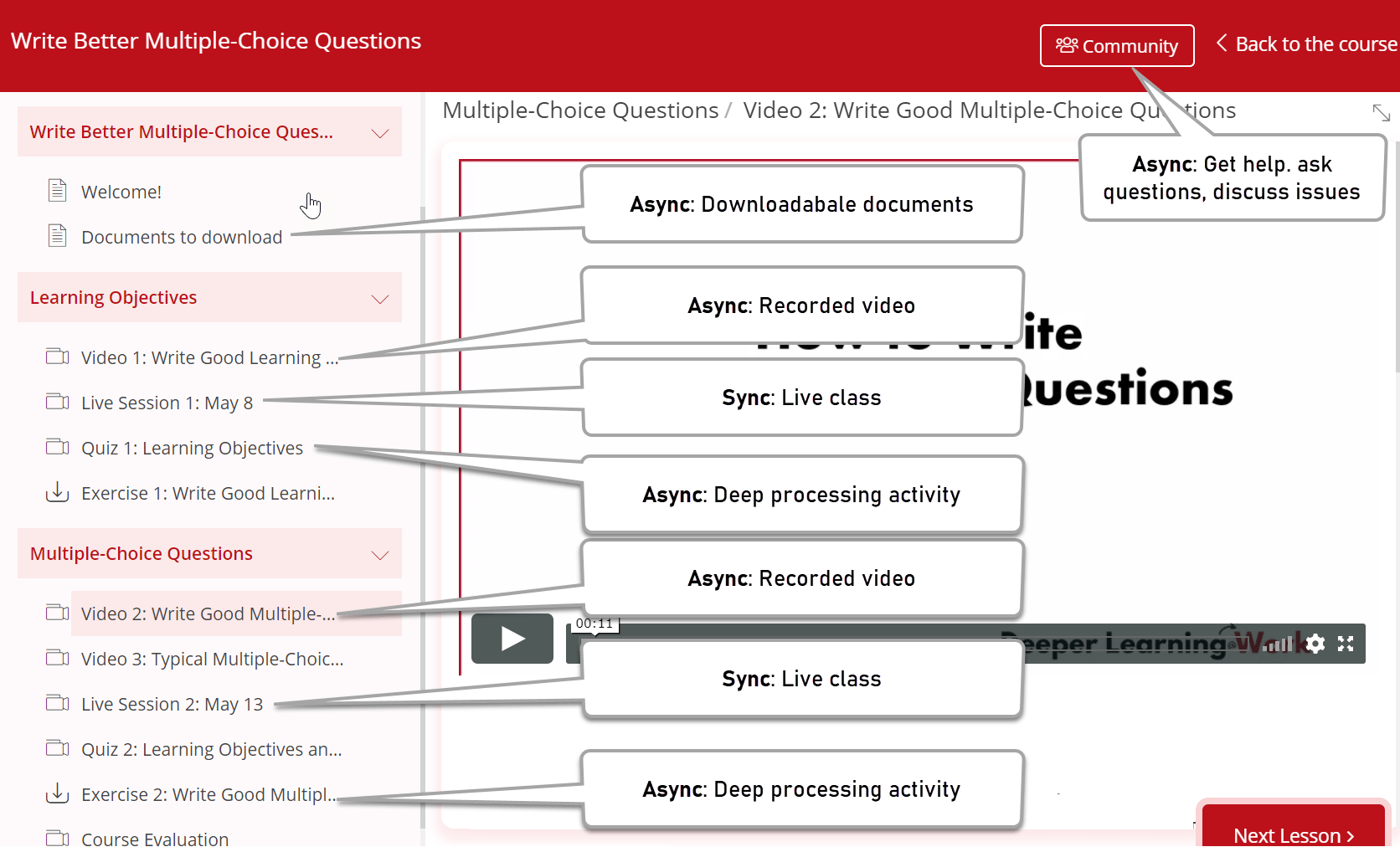

In my multiple-choice question-writing course, I use a wide range of async and sync components, as shown in this screenshot of the course curriculum page.

(Sync and sync components used in my blended multiple-choice questions curriculum page. Course development/delivery tool.)

Deep Processing

I want to call out the issue of deep processing, as it’s a supercritical issue in helping instruction transfer to the job. Deep processing involves intentionally making personal sense of what we are learning by:

- Evaluating how the information is personally meaningful

- Connecting what we are learning to what we already know

- Finding patterns and principles

- Analyzing the implications of what we are learning

Making personal sense of what we are learning may happen when participants are reading, watching, or listening to asynchronous elements, especially if the participant has a personal need to apply the content. But we shouldn’t leave deep processing to chance during instruction. We should include deep processing activities because they encourage long-term memory alterations (additions, changes, or corrections to what we already know). Altering long-term memory must occur to learn, remember, and apply.

Kirschner, Sweller and Clark tell us, “The aim of all instruction is to alter long-term memory. If nothing has changed in long-term memory, nothing has been learned.”

What can we do, as designers of learning experiences, to build in deep processing? Here are a few valuable deep processing activities for deeply processing new information.

1. Deep And Important Questions Asked Directly Or Through Quizzes (Shown In Chart Below)

| Check for Understanding | Build Deeper insights |

|

|

2. Valuable Activities, Including:

- Putting information into your own words

- Analyzing situations, problems

- Discussing issues, problems, decisions, uses

3. Practice With Assistance And Feedback

To see what this looks like in practice, we’ll consider how we might design in deep processing for instruction on blood sugar testing using a glucometer for newly diagnosed diabetics.

| Deep Processing Strategy | Examples for Blood Sugar Testing Course |

| Questions |

|

| Activities |

|

| Practice |

|

(Examples of deep processing activities)

When I teach people how to select deep processing activities, I ask them to list the most critical things and insights participants must remember, do, and grasp. The deep processing activities (as well as assessment items) I design typically come from these three.

Combining Asynchronous And Synchronous Learning

I’ve been facilitating a blended online conference session on the topic of these articles for the L&D Conference (attend next year!) By discussing these articles with interested participants, the following primary insights about combining asynchronous and synchronous have emerged.

- There’s a “sweet spot” for asynchronous and synchronous

Most content interactions (and individual processing) should ideally be done asynchronously and most social interactions (and group processing) should ideally be done synchronously. There are reasons why this may not work, of course, but it’s a good rule of thumb to start with. - Synchronous isn’t the same as face-to-face classroom

Moving online quickly makes sync seem like an obvious choice because it’s the most like the face-to-face classroom. While that is true, you cannot teach in the virtual classroom the way you teach in the face-to-face classroom. Research shows synchronous design and facilitation is quite different than classroom design and facilitation. It’s easy to do a poor job if you don’t design specifically for a virtual classroom. - Async as prep for sync

We can use asynchronous content to prepare people for really impactful synchronous activities (such as case studies, situations, discussions, application exercises, quizzes, and more). In my view, based on what research tells us, this is one of the major reasons for blending them! - Async elements can be repurposed

Async content elements can also be used outside of courses (performance support, answers to customer questions, etc.). - Increased processing time

Offering more time to process with asynchronous elements is especially important when cognitive load is high. This occurs with complex materials and when there is increased element interactivity. Offering async individual processing activities such as quizzes and scenarios helps people know that they got it.

I hope that this series of articles has helped you with one of the most difficult aspects of developing online courses: Selecting the right elements and the tools to deliver them. Many attending my session at the L&D Conference have discussed the need to add additional elements, and we’ve had great discussions about how to add needed async and sync elements.

If you are interested in my Select Valuable Online Interactions or my Write Better Multiple-Choice Questions courses, please add yourself to my email list. I’ll send you an email the next time these courses are available and you can also bring these courses to your organization.

References:

- Andrews, J. (1980). The verbal structure of teacher questions: Its impact on class discussion. POD Quarterly: Journal of Professional and Organizational Development Network in Higher Education, 2(3 & 4), 129–163.

- Bernard, R. M., Abrami, P.C., Wade, A., & Borokhovski, E. (2004). The effects of synchronous and asynchronous distance education: A meta-analytical assessment of Simonson’s “equivalency theory,” Association for Educational Communications and Technology, 27th, Chicago, IL.

- Clark, R. C. & Mayer, R. E. (2008). Learning by viewing versus learning by doing: Evidence-based guidelines for principled learning environments. Performance Improvement, 47(9), 5-9.

- Craik, F. I. M., & Lockhart, R. S. (1972). Levels of processing: A framework for memory research. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal behavior, 11, 671-684.

- Furst, E. (nd). Understanding ‘understanding.’ Teaching with Learning in Mind.

- Furst, E. (nd). Meaning first. Teaching with Learning in Mind.

- Hrastinski, S. (2008). Asynchronous and synchronous e-learning. Educause Quarterly, 4, 51-55.

- Kask, B., Wood, S. & Williams, B. (2014). Synchronous and asynchronous communication: Tools for collaboration.

- Kim, K. J., Bonk, C. J. Teng, Y. T., Zeng, T. & Oh, E. J. (2006). Future trends of blended learning in workplace learning settings across different cultures, 20th Annual Proceedings of the Association for Educational Communications and Technology, 176-183.

- Kalyuga, S. (2014). Managing cognitive load when teaching and learning e-skills. Proceedings of the e-Skills for Knowledge Production and Innovation Conference 2014, Cape Town, South Africa, 155-160.

- Kirschner , P.A. Sweller, J. & Clark, R. E. (2006). Why minimal guidance during instruction does not work: an analysis of the failure of constructivist, discovery, problem-based, experiential, and inquiry-based teaching. Educational Psychologist, 41(2), 75-86.

- Kirschner, P., & van Merriënboer, J. (2013). Do Learners Really Know Best? Urban Legends in Education. Educational Psychologist, 48(3), 169-183.

- Lupshenyuk, D. & Adams, J. (2009). Workplace learners’ perceptions towards a blended learning approach, International Journal of Social, Behavioral, Educational, Economic, Business and Industrial Engineering, 3(6), 761-765.

- Moore, M. (1997). Theory of transactional distance. in Keegan, D., (ed.) Theoretical Principles of Distance Education. Routledge, 22-38.

- Offir, B., Lev, Y., & Bezalel, R. (2008). Surface and deep learning processes in distance education: Synchronous versus asynchronous systems. Computers & Education. 51, 1172–1183.

- Sitzmann, T., Kraiger, K., Stewart, D., & Wisher, R. (2006). The comparative effectiveness of web-based and classroom instruction: A meta-analysis. Personnel Psychology, 59(3), 623-664.

- Stouppe, J. (1998). Measuring interactivity. Performance Improvement, 37(9), 19–23.

- Swan, K. (2001). Virtual interaction: Design factors affecting student satisfaction and perceived learning in asynchronous online courses. Distance Education, 22, 306-331.

- Sweller, J. (2010). Element interactivity and intrinsic, extraneous, and germane cognitive load. Educational Psychology Review, 22, 123–138.

- Walsh, J. A. & Sattes. B. D. (2015). Questioning for Classroom Discussion. Alexandria, Va., ASCD.