Asynchronous And Synchronous Interactions

What learning tools do you need to support needed learning interactions in your organization? In Part 1, I discussed tools that support digital learning that are used asynchronously (self-paced, when and where the user chooses) and synchronously (live, at the same time for all users). Both modes of learning support learning, but differently, according to research.

In Part 2 (this article), I’ll analyze how asynchronous and synchronous tools support different types of learning interactions. And I’ll describe the best ways to use asynchronous and synchronous learning.

Some key ideas discussed in Part 1 that are helpful for understanding the ideas in Part 2:

|

Interaction—>Processing

Learning interactions involve mentally processing what is being learned. Moore described the need for both content and social interactions in technology-driven instruction. I’ll be discussing common content and social interactions in this section.

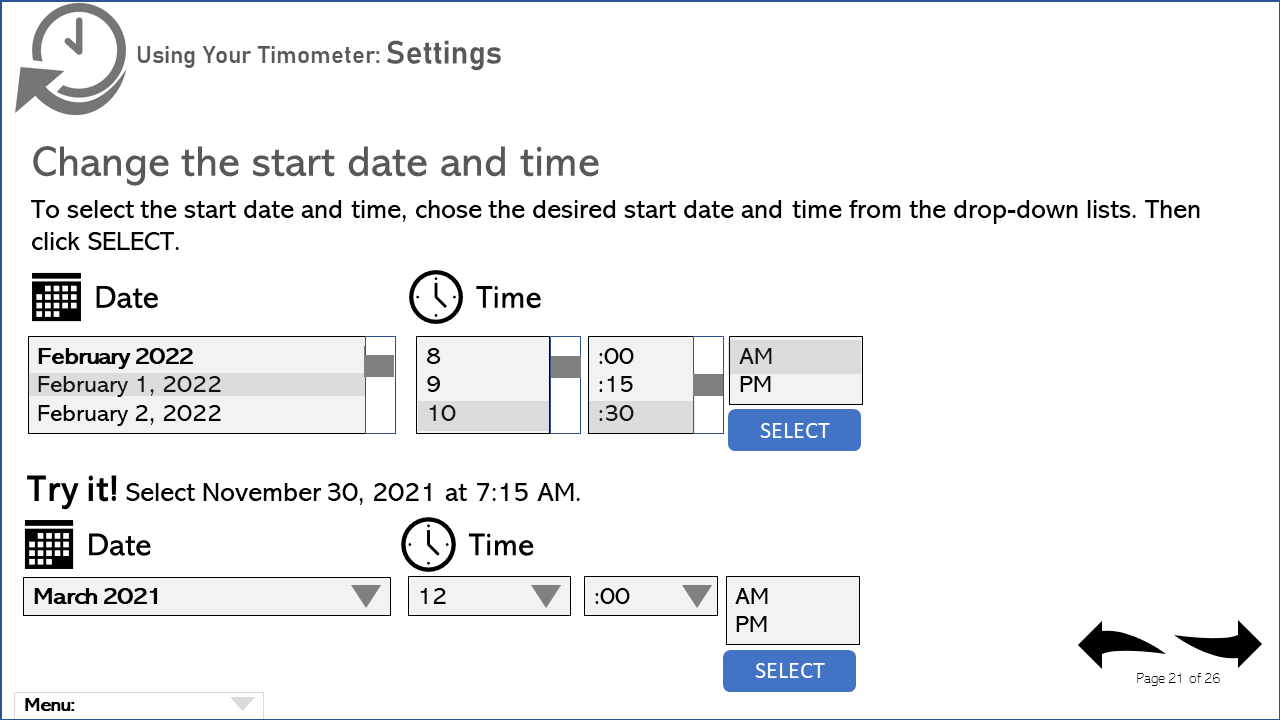

Content interactions prompt participants to interact with the content typically by reading, watching, listening, and doing self-paced activities. For example, common content interactions in asynchronous eLearning are video followed by multiple-choice questions to gauge understanding. The example below shows an asynchronous content interaction that asks the participant to try changing the start date and time.

(Example content interaction in an asynchronous course)

(Example content interaction in an asynchronous course)

Social interactions are interactions between people. They include interactions among participants, such as discussions in an asynchronous discussion forum, and between the instructor/facilitator and participants, such as answering participant questions in chat.

Interactions with the instructor are considered highly desirable because instructors should promote and maintain interest, offer demonstrations and behavior modeling, answer questions, prompt participants to understand and use, assess and fix understanding, support and encourage, and so much more.

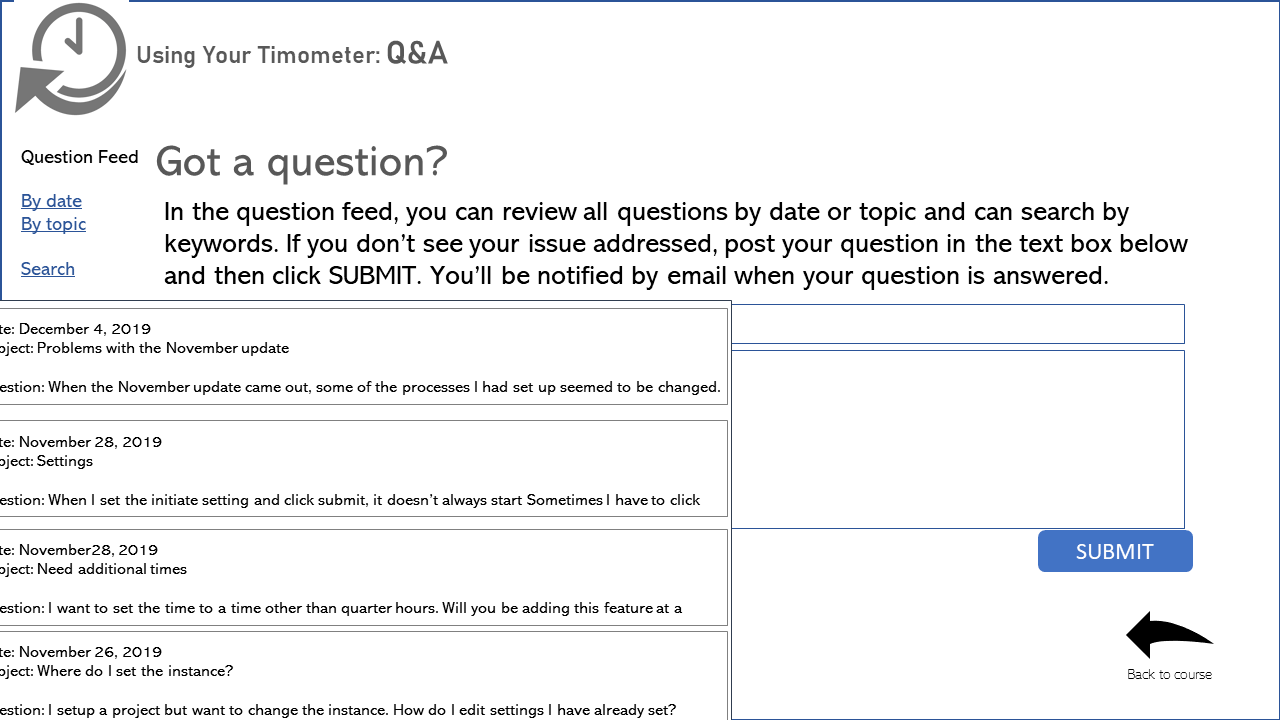

In workplace asynchronous learning, where there is often no social interaction, we should consider offering ways to get questions asked, at a minimum. The example below is an asynchronous course that includes a question and answer element.

(Example Q&A interaction in an asynchronous course)

(Example Q&A interaction in an asynchronous course)

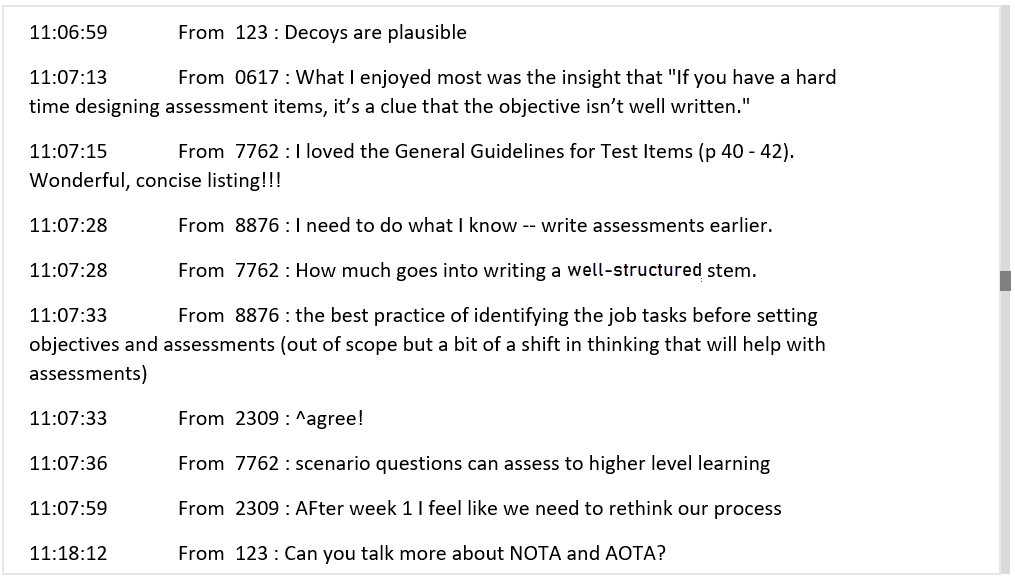

Synchronous courses using virtual classroom or webinar tools often have integrated chat and question pods where participants can ask and answer questions. These tools can also be used to discuss issues and insights and offer input and support. These outcomes are difficult to gain without these interactions.

Below is a portion of a chat interaction from one of the live sessions in one of my blended online courses. (I changed names to numbers to hide identity.) I asked participants to tell me the most important thing they learned that week. You can see that this deep question helped them remember earlier content and share it with others. It also gave them a chance to let me know what was still confusing.

(Example portion of a chat interaction from a live session in one of my blended courses)

(Example portion of a chat interaction from a live session in one of my blended courses)

Here are some typical and valuable content interactions that are used to help the participant watch, read, and listen to content and prompt deep processing of that content.

| Watch, read, listen | Prompt deep processing | |

| Narrated slide presentation | Scenario and case analysis | |

| Software or product demo | Answer questions | |

| Guided tour | Perform a task | |

| Stories | Game | |

| Insights and resources | Simulation |

Here are some typical and valuable social interactions among participants and between the instructor and participants.

| Among participants | With the instructor | |

| Role-paying | Question and answer | |

| Group analysis | Polls | |

| Personal experiences | Deep questions | |

| Insights and resources | Check for understanding |

Moore tells us it is a mistake to attempt to push everything into a single tool as it may constrain the types and depth of possible interactions. For example, in the virtual classroom, the content is moving at a specific, Instructor-Led pace, it may leave some people behind if they are not able to keep up.

Bernard’s meta-analysis supports my assertion that the right kinds of content and social interactions help participants mentally engage with the content in order to substantially improve learning outcomes.

A critical outcome from deeply processing the content is "changes to memory," which is needed to learn, remember, and apply. Furst explains that deep processing supports:

- Knowing

Where new concepts are added to what is already known in long-term memory. - Understanding

Where we create associations between what we already know and new content, so we know how to use them. - Using

Where the additions and changes to memory are made available for use.

According to Clark and Mayer, the mental activity used in deep processing is what leads to learning so they cannot be considered optional. When people mentally process movies, books, and podcasts, for example, it is not the content that leads to learning but the mental processing of that content. Whether the content is passive or active is not the primary issue: We can and do learn from both. The primary issue is the depth processing that occurs.

Deep processing is critical to move use from simply knowing to ability to use. Asynchronous and synchronous tools provide different means for supporting these deep processing interactions.

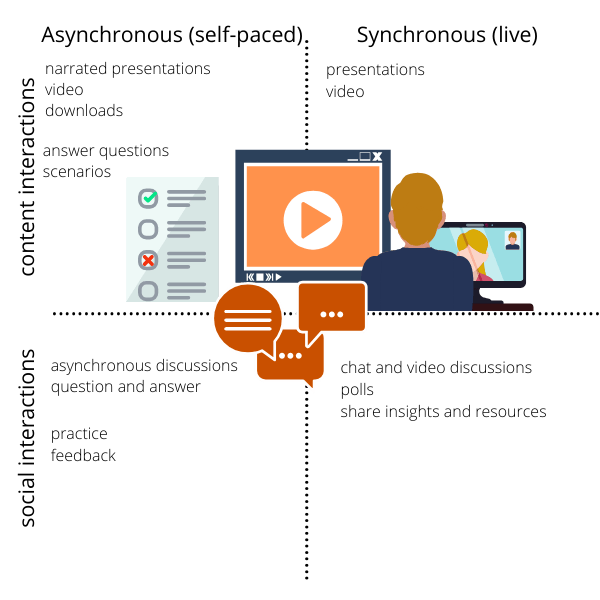

Asynchronous Versus Synchronous Interactions

In the previous section, I described the need for content and social interactions. Various asynchronous and synchronous tools support these interaction types. Below, are typical content and social interactions for learning that occur in asynchronous and synchronous tools.

We can promote important mental processing using a variety of interactions. Here are some of the interactions that research points to as especially effective to encourage deep mental processing.

- Restate important insights using your own words

- Organize content to show how concepts relate to each other (using outlines, mind maps, etc.)

- Answer important questions (“When should we…?”)

- Solve relevant problems

- Analyze which principles apply

- Use needed resources and tools

Selecting Asynchronous And Synchronous Tools To Support Learning

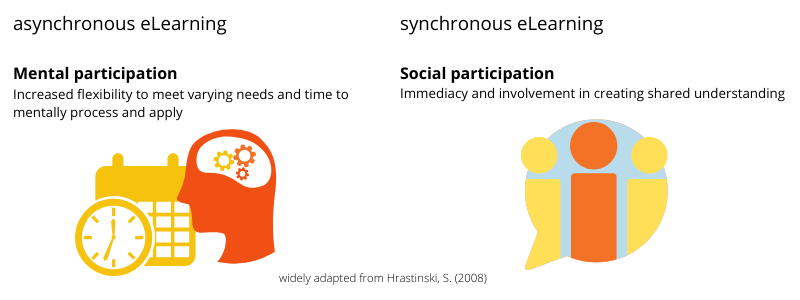

We can use asynchronous and synchronous tools to facilitate needed interactions, but some tools are clearly better suited for some interactions and less suited for others. The evidence described by Anderson, Hrastinski, Kask, Offir, and others makes clear the best uses and limitations of asynchronous and synchronous learning. The following table merges what evidence shows. It isn’t meant to be complete but rather show some of the primary advantages and limitations which can help you make good choices about when to use each.

|

|

Asynchronous Learning (self-paced) | Synchronous Learning (live) |

| Advantages | Flexibility

Time

|

Social interaction

Immediacy

|

| Limitations | Isolation

|

Inflexibility

Technical

|

(Advantages and limitations of asynchronous and synchronous learning)

I rolled up the best use cases for asynchronous and synchronous below (widely adapted from Hrastinski, adding insights from other research).

Conclusion

One of the best ways to use the information in this article to make decisions about asynchronous and synchronous tools is to analyze the following:

- Where would flexibility and time to process be most beneficial?

Select asynchronous tools that allow for flexibility and processing time. Example tools include online and downloadable content and asynchronous discussion forum. - Where would immediacy and social interaction be most useful?

Select synchronous tools that allow for immediate support and feedback as well as sharing insights and resources. Examples include virtual classroom tools that allow for live video, audio, and chat.

Consider signing up for my email list (top of www.pattishank.com) as I hope to hold free live sessions to discuss the content in Part 1 and Part 2 and answer questions about how to apply it to your situation. I’ll notify everyone on my list about these sessions shortly.

In Parts 3 and 4, I’ll go into more detail about asynchronous and synchronous learning.

References:

- Adams, Rebecca L. (2010). Design practices business organizations employ to deliver virtual classroom training, Graduate Research Papers. 122.

- Anderson, L. A. (nd). The effect of synchronous and asynchronous communication on social presence and isolation in online education.

- Bernard, Robert & Abrami, Philip & Borokhovski, Eugene & Wade, C. Anne & Tamim, Rana & Surkes, Michael & Bethel, Edward. (2009). A Meta-Analysis of Three Types of Interaction Treatments in Distance Education. Review of Educational Research, 79(2), 1243-1288.

- Bower, M. (2008). Designing for interactive and collaborative learning in a web conferencing environment. Doctoral dissertation, Macquarie University, Sydney.

- Bower, M. (2011). Synchronous collaboration competencies in web-conferencing environments—their impact on their learning process. Distance Education, 32(1), 68-83.

- Bower, M., Dalgarno, B., Kennedy, G., Lee, M., & Kenney, J. (2014). Blended synchronous learning. A handbook for educators. Sydney: Office of Learning and Teaching, Department of Education.

- Bower, M., Dalgarno, B., Kennedy, G. E., Lee, M. J. W., & Kenney, J. (2015). Design and implementation factors in blended synchronous learning environments: Outcomes from a cross-case analysis. Computers & Education, 86, 1-17.

- Boyle, T., Bradley, C., Chalk, P., Jones, R., & Pickard, R. (2003). Using blended learning to improve student success rates in learning to program. Journal of Educational Media, 28(2/3), 165-178.

- Chou, C. C. (2002). A comparative content analysis of student interaction in synchronous and asynchronous learning networks, Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences.

- Clark, R. C. & Mayer, R. E. (2008). Learning by viewing versus learning by doing: Evidence-based guidelines for principled learning environments. Performance Improvement, 47(9), 5-9.

- Dziuban, C. D., Hartman, J., & Moskal, P. (2004). Blended Learning. Educause Center for Applied Research Bulletin, 7, 1-12.

- Furst, E. (nd). Introduction: Learning in the brain. Teaching with Learning in Mind.

- Furst, E. (nd). Understanding ‘understanding.’ Teaching with Learning in Mind

- Furst, E. (nd). Meaning first. Teaching with Learning in Mind.

- Giesbers, B., Rienties, B., Tempelaar, D., & Gijselaers, W. (2013). A dynamic analysis of the interplay between asynchronous and synchronous communication in online learning: The impact of motivation. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning.

- Grant, M., & Cheon, J. (2007). The value of using synchronous conferencing for instruction and students. Journal of Interactive Online Learning, 6(3), 211-226.

- Haidet, P., Morgan, R.O., O’Malley, K., Moran, B.J., & Richards, B.F. (2004). A controlled trial of active versus passive learning strategies in a large group setting. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 9, 15–27.

- Hrastinski, S. (2008). Asynchronous and synchronous e-learning. Educause Quarterly, 4, 51-55.

- Hsieh, Y. H. & Tsai, C. C. (2012). The effect of moderator’s facilitative strategies on online synchronous discussions, Computers in Human Behavior, 28(5), 1708–1716.

- Hurst, B., Wallace, R., & Nixon, S. B. (2013). The impact of social interaction on student learning. Reading Horizons: A Journal of Literacy and Language Arts, 52(4), 375-398.

- Kask, B., Wood, S. & Williams, B. (2014). Synchronous and asynchronous communication: Tools for collaboration. http://etec.ctlt.ubc.ca/510wiki/Synchronous_and_Asynchronous_Communication:Tools_for_Collaboration

- Kim, K. J., Bonk, C. J. Teng, Y. T., Zeng, T. & Oh, E. J. (2006). Future trends of blended learning in workplace learning settings across different cultures, 20th Annual Proceedings of the Association for Educational Communications and Technology, 176-183.

- Lupshenyuk, D. & Adams, J. (2009). Workplace learners’ perceptions towards a blended learning approach, International Journal of Social, Behavioral, Educational, Economic, Business and Industrial Engineering, 3(6), 761-765.

- Moore, M. (1989). Editorial: Three types of interaction, American Journal of Distance Education, 3:2, 1-7.

- Offir, B., Lev, Y., & Bezalel, R. (2008). Surface and deep learning processes in distance education: Synchronous versus asynchronous systems. Computers & Education. 51, 1172–1183.

- Shank, P. (2019). Blended learning in today’s workplace. eLearning Industry.

- Sitzmann, T., Kraiger, K., Stewart, D., & Wisher, R. (2006). The comparative effectiveness of web-based and classroom instruction: A meta-analysis. Personnel Psychology, 59(3), 623-664.

- Thurmond, V. A., & Wombach, K. (2004). Understanding interactions in distance education: A review of the literature. International Journal of Instructional Technology and Distance.