How To Build A Foundation That Supports Learning And Performance

Researchers Saurabh Bhargava, George Loewenstein, and Justin Sydnor studied almost 24,000 people in a U.S. Fortune 100 organization who needed to pick a new health plan. The researchers found that most of the people picked poorly. According to their analysis, most people simply didn’t have the needed knowledge to analyze the plans. This makes total sense, as research shows that adequate and accurate prior knowledge is one of the most critical drivers of learning and performance.

Learning and performance outcomes depend a LOT on what we already know. When we have more knowledge, we can use it to analyze differences and make decisions. Without it, we struggle with the information presented. Learning is slower. People tend to give up easily when they are confused and can’t make sense of the information. These issues are likely contributors to the research on making poor health plan buying decisions.

I’ve had people tell me that we don’t need to remember anything; we can simply look things up when we need to. Sure, we can look up things. But having more knowledge helps us know what to look up, understand what we look up, and put it to use. Without that, we struggle.

In analyzing the cost and coverage differences between health plans, for example, we call on health insurance foundational knowledge to analyze the important aspects of a health plan for our specific needs. Some key terms and concepts needed (I am using US health plan terminology because it’s what I know) include:

- Concepts:

- Cost sharing

- Out-of-pocket costs

- Selected terms:

- Coinsurance

- Copayment

- Covered charges

- Deductible

- Formulary

- In-network

- Out-of-network

- Out-of-pocket maximum

Without understanding these terms and concepts, how they are related, and how to apply them, it is quite difficult to compare plans.

People necessarily start learning about most subjects with little or no foundational knowledge and they are, as a result, at a disadvantage. That’s why it’s critical that workplace learning practitioners intentionally help people gain this knowledge. And since learning with little or no foundational knowledge is difficult, we must also design instruction for people who are new to a subject to build foundational knowledge that is accurate and adequate and not overwhelming. (Misunderstandings damage the ability to learn.)

Prior Knowledge Benefits And Challenges

Prior knowledge makes it easier to:

- Perceive what is more and less important

- Make sense of new information when processing it in working memory

- Work around the significant limitations of working memory

- Store what is learned in long-term memory with related information

- Retrieve and use what is stored to use when performing

When someone has little or no prior knowledge about what they are learning, they have numerous difficulties while learning. For example, when analyzing health plans, unfamiliar terminology makes the content hard to understand. Most people do not take the time to look up unfamiliar words—they keep going—reducing comprehension.

Some people think that the solution to this problem is simple. Define the term the first time it is used. But that’s a simple solution to a not-so-simple problem. Ever forget the name of someone you were introduced to five seconds earlier? Right. Same issue. People are not-so-likely to remember definitions just because we provided it elsewhere. And since people tend to skim and look for things that matter most to them, they might easily miss the definition. This is why strategies that help people remember and use key words and concepts first can get around this problem, especially if there are a lot of them.

Building The Foundation

How do we help people build needed foundational knowledge? We can start by analyzing people’s level of prior knowledge, so we are not making assumptions about what they know. Research clearly shows that we make it easier to learn when we meet the specific (and often different) needs of different audiences. For those new to the topic, we intentionally and carefully determine the terms and concepts they need to build a foundation for further learning.

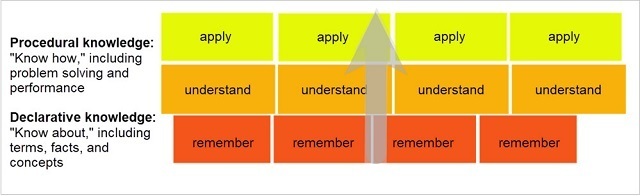

Learning for application is like building a house. It is built on a foundation, from the bottom up (Figure 1). First, we learn facts and concepts (remember level). Next, we build understanding around these facts and concepts (understand level). And then we build on understanding so we can apply.

Figure 1. Growth of knowledge from remembering to understanding to applying (from Patti Shank’s Design for Better Training Outcomes workshop)

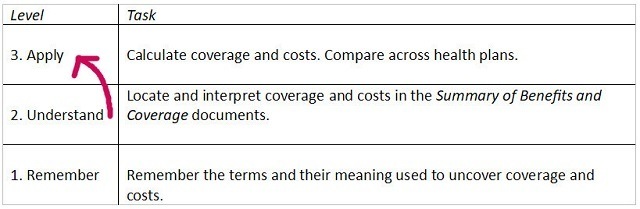

Table 1 describes specific tasks that make up remember, understand, and apply levels for someone trying to analyze the differences in cost and coverage between plans for their most used medical services.

Table 1. Tasks for analyzing healthcare coverage and costs at each level of knowledge

Each level is needed for performance at the next level. The top level (apply) is cumulative.

The Bottom Line

What we already know is one of the most critical elements of consideration when designing instruction. If you read my other articles on eLearning Industry, you’ll notice a pattern of slightly to largely different research-driven tactics for people with less and more prior knowledge.

In a recent webinar, one of the participants asked, “Does this mean that we need far more time to give people new to the topic a good foundation rather than pushing tons of information on them?” Bingo. Yes, indeed.

Next month, I’ll discuss specific research-driven tactics that help us work with prior knowledge when designing instruction.

References:

- Bhargava, S., Loewenstein, G., & Sydnor, J. (2017). Choose to lose: Health plan choices from a menu with dominated option, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 132 (3), 1319–1372.

- Dochy, F., De Rijdt, C., & Dyck, W. (2002). Cognitive prerequisites and learning. Active Learning in Higher Education, 3(3) 265–284.

- Hailikari, T., Katajavuori, N., & Lindblom-Ylanne, S. (2008.) The relevance of prior knowledge in learning and instructional design. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 72 (5) Article 113.

- Kirschner, P. A., Sweller, J., & Clark, R. E. (2006). Why minimal guidance during instruction does not work: An analysis of the failure of constructivist, discovery, problem-based, experiential, and inquiry-based learning. Educational Psychologist, 41(2), 75-86.

- Shank, P. (2017). Manage Memory for Deeper Learning.

- Stockard, J., Wood, T. W., Coughlin, C., & Khoury, C. R. (2018). The effectiveness of direct instruction curricula: A meta-analysis of a half century of research. Review of Educational Research.

- Sweller, J., Ayres, P. L., Kalyuga, S. & Chandler, P. A. (2003). The expertise reversal effect. Educational Psychologist, 38 (1), 23-31