Discussing The Nature Of Realistic Training

Ruthie, an eLearning freelancer, is working with a new client to design training on buzzed driving. Buzzed driving means driving with a blood alcohol concentration (BAC) technically under the legal limit but still dangerous. She and the client have agreed to use interactive scenarios for most of the training. Participants will work through stories involving people who drink in a variety of situations (parties, work events, family gatherings, and so on).

Ruthie is has developed some scenarios but she has 2 questions she wants to answer from learning research before she starts building the training:

- How much realism should her scenarios involve? (Look and feel, situations, and so forth)

- Should feedback come primarily from the consequences of the actions people take in the scenario or from learning feedback (for example, an outside voice or guide who explains what the participant did wrong)?

In this article, I’ll discuss what research tells us about the nature of realism in training. This information can be extremely valuable to improving learning outcomes, especially transfer of learning to the workplace. Most research about transfer shows that transfer doesn’t happen easily. But luckily, there are ways we can design for better transfer. And realism can figure into better transfer.

I’ll answer most of question one in this article and next month I’ll discuss a few extra parts of answer one and answer question two. I think you’ll agree that the applications are fascinating and able to be put into action right away.

Is Realism Important?

Training research shows that it is easier for people to more actively engage with training when they see specific purposes for the challenges of learning, practicing, using feedback to improve, and applying what they learn. Relevance creates an environment for training to transfer to the workplace, which is ordinarily a difficult process. Relevance, it so happens is the real “engagement”. People find training relevant when it:

- Obviously connects to work tasks.

- Helps them with real work challenges.

- Teaches them to avoid and fix errors.

- Helps them improve existing and needed work skills.

- Is at the right level (matches what they already know and can do).

The most obvious implication of relevance is that we need to understand the work people do, their challenges, typical errors, and skill challenges to meet their training needs.

Learning is cumulative and builds on what people already know. We must take differences in what people know and can do into account in training. When Ruthie builds training she will likely want to build slightly different scenarios for people who have had a DWI or DUI (driving while impaired or driving under the influence) and people who haven’t. Different levels of prior knowledge and skills often mean different training needs. For example, people who have never had a DUI or DWI may not know the difference, but people who have dealt with one usually do. So, the starting points are different. Ruthie will need to determine the differences in needs and figure out how these differences should affect the scenarios.

Research shows that memory is quite context sensitive and we remember context along with memory. Have you ever heard an old song and remembered how old you were and where you were when you heard it? That’s context sensitive memory at work. To make it easier for learning to transfer to the job, we want to use real job contexts during instruction. People remember knowledge and skills in the context they use them better than they remember them without context. But what kinds of contexts are important? We’ll discuss that next.

Realism… What Is It Exactly?

When I explain the need for realism during training, people often ask if training should look, act, and feel exactly like the job. And they are surprised when my answer is this: Typically, no. We don’t want to add all possible realism elements. Just ones that most matter on the job. We’re talking about a specific term: Fidelity.

Fidelity (as we are using it here) means how much training matches critical elements of the job environment. The table below shows different elements of fidelity and describes what they mean:

| Elements | Description |

| Physical | How much training looks, sounds, and feels like the job |

| Functional | How much training acts like the job (generally used for how things work, such as tools and systems) |

| Cognitive | How much training requires people to think like they will think on the job |

| Psychological | How much training induces similar emotional responses as on the job, such as time pressure, stress, or conflict |

| Physiological | How much training induces similar emotional responses as on the job, such as time pressure, stress, or conflict |

Many training developers feel like training should look like the actual training environment (physical fidelity). So, they may spend a lot of effort making sure screens look like realistic office buildings, with typical office people. But doing this can be time consuming and participants may be drawn away from the task at hand while noticing shiny objects and the hair styles of the people onscreen.

The question is this: Which types of fidelity are beneficial in training and which aren’t? The answer is clear but not simple: The type(s) of fidelity most beneficial for learning (especially for transfer of skills to the workplace) are those that match the desires training outcomes.

We shouldn’t add other types to for more realism because those added realistic elements can be distracting to the senses. Overwhelming sensory information makes it harder to learn. So, fidelity is good when appropriate and problematic if distracting. Well, wait. If dealing with distractions is part of the learning objective, add the appropriate distractions in. And if the person is new to the task, start without distractions and slowly add them in.

Ready to think this through? Below are 2 learning objectives for the third lesson in Ruthie’s buzzed driving training:

- While sober, make a list of at least 5 reasons not to drink and drive.

- Plan a minimum of 2 safe ways to get home before deciding to drink.

Which type(s) of fidelity is/are most critical to the learning objectives above? [Please put your hand over the shaded answer and write down your answers before continuing. You will learn more by thinking through this issue than reading the answer before thinking it through!]

Patti’s answer:

The types of fidelity I think are most important are cognitive fidelity and psychological fidelity. Physical fidelity is not important because how the scene looks is not at issue. Cognitive fidelity is critical because the most important issue is thinking through reasons and what to do. Psychological fidelity is also important because creating tension over having good reasons and ways to get home can be helpful.

How does my answer match with yours? Did you have different assumptions that led to different answers?

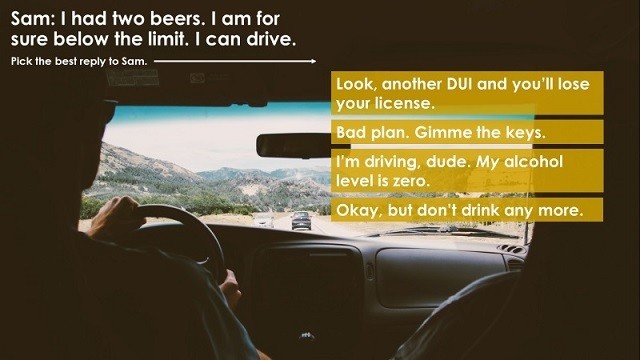

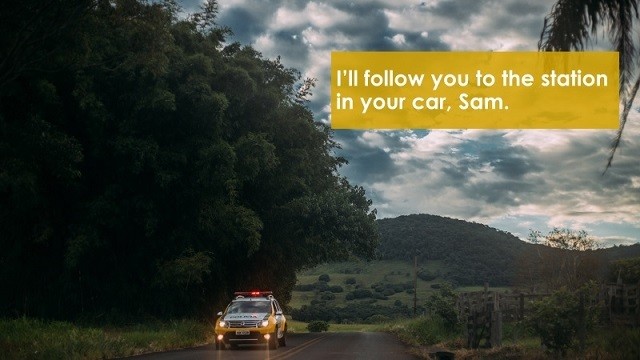

I thought you might enjoy seeing 2 examples of buzzed driving scenario scenes from my upcoming book, Practice and Feedback for Deeper Learning:

So, why the visually realistic scenes if cognitive and psychological fidelity are most needed? They are dark and add tension without getting caught up in visual details. The police car lights in the second scene make it clear that Sam was caught, but yeah, the scenes would have worked without visuals. Like most developers, I can get carried away with visuals. ;)

Which type(s) of fidelity do you think is/are most critical to these learning objectives? I’ll share my answers next month.

| Learning objective | Types of fidelity needed? |

| Replace paper in the XYZ-type copier. | |

| Fix a paper jam in the XYZ-type copier. | |

| Create headings using MS Word Heading Styles. | |

| Give a colleague constructive feedback on his report. | |

| Create the correct code for each medical diagnosis. |

If you have questions, ask away. Or start a discussion on Twitter by posting to @pattishank and @elearnindustry. See you soon!

References:

- Alexander, A. L., Brunyé, T., Sidman, J., & Weil, S. A.(2005). From Gaming to Training: A Review of Studies on Fidelity, Immersion, Presence, and Buy-in and Their Effects on Transfer in PC-Based Simulations and Games. DARWARS Training Impact Group.

- Burke, L. A. & Hutchins, H. M. (2007). Training transfer: An integrative literature review, Human Resource Development Review, 6, 263–96 (PDF download)

- Grossman, R. & Salas, E. (2011). The transfer of training: What really matters. International Journal of Training and Development, 15(2), 103-120.

- Jentsch, F. & Bowers, C. A. (1998). Evidence for the Validity of PC-based Simulations in Studying Aircrew Coordination. International Journal of Aviation Psychology, 8(3), 243-260.

- Salas, E., Wilson, K. A., Priest, H. A. and Guthrie, J. W. (2006). Design, Delivery, Evaluation, and Transfer of Training Systems, in Handbook of Human Factors and Ergonomics, Third Edition (ed G. Salvendy), Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.