Learning Styles: The Enduring Myth That Weakens L&D

In Learning and Development circles, it's common to hear phrases like:

- "We need to tailor this for visual learners."

- "She's more of a kinesthetic type, so let's build an activity."

- "We want to cover all learning styles to be inclusive."

It sounds thoughtful—even learner-centered. But there's a problem: None of it improves learning outcomes.

The idea of "learning styles"—that individuals learn better when instruction matches their personal sensory preferences—has been around for decades. But research has repeatedly shown that this approach is unsupported by scientific evidence. Even worse, continuing to use it can reduce program impact, waste design time, and chip away at L&D's credibility within the business. If L&D is serious about driving performance and business outcomes, it's time to stop designing for preferences and start designing for how people actually learn.

What The Research Really Says

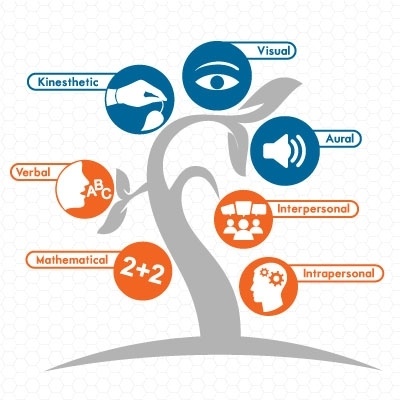

The "learning styles hypothesis" suggests that people have preferred ways of learning—visual, auditory, kinesthetic, etc.—and that instruction should be matched to those preferences for optimal learning. But this idea has failed to hold up under scrutiny.

In 2008, a major review led by cognitive psychologist Harold Pashler concluded: "There is no adequate evidence base to justify incorporating learning-styles assessments into general educational practice." Subsequent meta-analyses and replications have supported this. While people certainly have preferences, adapting instruction to match those preferences has no measurable effect on learning performance.

Here's why:

- Preferred styles don't necessarily reflect cognitive strengths.

- Matching instruction to a style doesn't improve comprehension or retention.

- The type of content—not learner preference—should drive instructional modality.

For example, learning to repair an engine may benefit from visual diagrams and hands-on manipulation, regardless of the learner's "style." Preferences may influence engagement, but they don't influence learning effectiveness.

Why The Learning Styles Myth Persists

Despite widespread debunking, learning styles are still mentioned in training requests, eLearning designs, and even university programs. So why does the myth endure?

- It feels intuitive

Everyone has preferences, and it's easy to assume those preferences should dictate learning. But as any coach knows, comfort isn't always where growth happens. - It signals personalization

In an age of learner-centered design, organizations want to show they're adapting to individual needs. Learning styles seem like an easy way to "check the box"—even if they miss the mark. - It's easy to understand

Compared to models like cognitive load theory or retrieval practice, learning styles are simple and catchy. This simplicity makes them easier to explain to stakeholders, even if they're inaccurate.

Unfortunately, continuing to rely on learning styles creates a false sense of personalization while diverting energy from evidence-based L&D practices that truly improve learning outcomes.

The Real Cost Of Designing L&D For Learning Styles

Learning styles may seem harmless, but they come at a cost:

1. Design Inefficiency

Instructional Designers may create multiple redundant formats for each "style," leading to bloated development timelines and unnecessary complexity.

2. Reduced Instructional Impact

Designers spend time adapting to preferences instead of aligning content with task requirements or cognitive processes, undermining effectiveness.

3. Misdirected Resources

Effort goes into assessing styles, designing tailored materials, and justifying choices that have no proven return on learning.

4. Weakened Professional Credibility

As L&D aims for greater strategic influence, it must be grounded in research. Clinging to debunked models undercuts our legitimacy in the eyes of executives, business partners, and learning-savvy employees.

What To Do Instead: 6 Evidence-Based Principles

Dropping learning styles doesn't mean ignoring learner diversity. It means designing in ways that are proven to enhance retention, comprehension, and transfer. Here are six alternatives to drive real impact:

1. Design For Cognitive Load

Overloading working memory interferes with learning. Break content into manageable chunks, reduce extraneous elements, and use visual and auditory input strategically (not based on learner preference).

2. Use Dual Coding And The Modality Principle

Combine visuals and narration to enhance understanding (not text and narration, which can split attention). Use modality based on content type—e.g., animations for process, text for definition—not individual preference.

3. Prioritize Prior Knowledge

Adjust difficulty and support based on what learners already know. Novices need worked examples; experts benefit from problem solving. This leads to better performance outcomes than style-matching ever could.

4. Support Active Retrieval And Spaced Practice

Use quizzes, scenario branching, and real-world reflection to prompt memory retrieval. Spaced intervals between learning and review sessions dramatically boost retention.

5. Create Psychological Relevance

Connect learning to the learner's context, identity, and role. Motivation and meaning fuel attention and transfer, far more than modality alignment.

6. Design For Transfer, Not Just Engagement

Real-world practice, feedback, and reinforcement matter more than style-fit. Build cues, habit loops, and manager follow-up into the design for sustained behavior change.

How To Shift Your Organization Away From The Myth

Transitioning your team or organization away from learning styles may take more than just a memo. Here are practical strategies to manage that shift:

1. Educate Stakeholders

Share short, evidence-backed articles or infographics explaining the research. Avoid shaming; focus on showing better alternatives.

2. Audit Existing Programs

Identify where learning styles are embedded in intake forms, templates, or eLearning builds. Replace them with questions about context, barriers, and performance conditions.

3. Use Business Language

Frame your argument in terms of efficiency, effectiveness, and return on effort. Stakeholders respond to outcomes, not theories.

4. Pilot A Shift In One Program

Redesign a course with cognitive science principles. Measure the results and share them widely. Real examples are more persuasive than academic citations.

Final Thought: L&D Deserves Better

Learning and Development is evolving. Our seat at the strategic table depends on credibility, evidence, and results. Continuing to lean on myths like learning styles sends the wrong message about our discipline.

The good news? When we move past outdated models, we open space for innovation—driven by science, not habit. Great learning design is not about catering to preferences. It's about aligning with how people actually learn, change, and grow. And that's where L&D shines brightest.