How To Fix Business Problems Using Training The Right Way

A bear, a teacher, and a chicken walk into a bar together. The bartender looks up and yells “We need training and we need it right now!”. Like my silly joke, too much training simply doesn’t make sense. When stakeholders (the people who have a problem and assume that training will fix it) ask for training, and we simply build and deliver training to them, we’re rolling a bunch of business problems into one misguided package. Here are 3 things wrong with that package.

- What? We don’t even bother to first analyze if what we provide will solve their problem? Does that sound like something professionals do? (Would it be professional practice for your dentist to decide what’s wrong with your tooth with no analysis?)

- Training is expensive. Especially when it doesn’t fix the problem. (Would you want to deal with and pay for a root canal if you didn’t need one?)

- If we’re primarily content developers, we won’t have jobs in the future and our skillset will be continually devalued. (It is already heading in that direction.)

In the last two articles, I’ve explained the types of issues that cause most performance problems and what types of interventions can help fix them. If you haven’t yet read those articles, they’ll provide a good foundation for what I’m about to discuss. When I talk to people about helping stakeholders solve non-training types of problems, I’m often asked two questions:

- How do I determine which type of problem it is?

- How can I get stakeholders to move towards fixes, rather than simply ask for training?

Let’s start with the second question first, because it starts the ball rolling on answers to the second question.

Moving Towards Fixes

Reframing training requests starts with how you answer requests for training. The mindset for the two approaches is different. A problem-solving mindset is quite different than a training mindset and the following question sets show the difference.

| Training Mindset | Problem-Solving Mindset |

|

|

Rather than answer requests like you normally do, start with some simple questions that try to get at what the stakeholder already knows about the problem. These questions are some of the most helpful starting questions for me.

- What made you realize there was a problem/need/issue?

- What have you already tried to fix this problem/need/issue? (What has worked? You’ll want to align your work with other fixes. What didn’t? You need to understand what failed and why.)

- What else are you already doing to fix this problem/need/issue? (You’ll want to align your work with other fixes.)

- How will you know when this problem/need/issue has been fixed? (What outcomes are they looking for? The answer may help determine how important this problem is.)

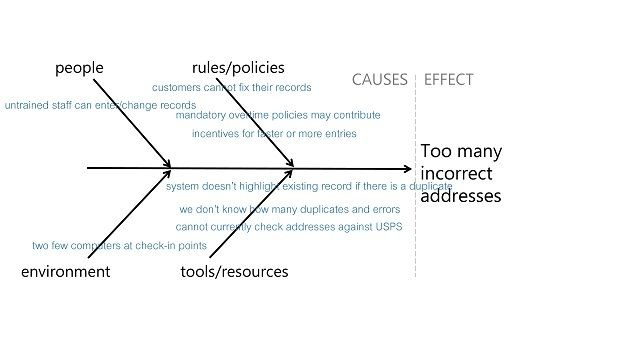

If you’ve ever been involved in quality improvement training, you will remember using something called a fishbone diagram (also known as a cause–and–effect diagram) to gather what stakeholders see as contributors to a given problem. Below I show an example from some initial brainstorming with the reasons for errors on customer addresses. Address errors may sound like no big deal, but when you are sending important information and bills to the wrong address, think again!

Stakeholders (such as managers, billing people, customer service trainers, and people who maintain the billing systems) initially requested widespread training on inputting customer addresses, but after a brief brainstorming session, they realized that fixes for the problem were broader and training wasn’t the primary solution. (Although I do see a possible training issue. You? Tell me in comments, okay?)

What you are trying to do is find underlying contributing factors for the problem. There are often many contributing factors to business problems, as you see in this example. Then stakeholders need to determine which they want to collect additional information about. After selecting factors to fix, additional work is needed to see if the problem has lessened.

What you are trying to do is find underlying contributing factors for the problem. There are often many contributing factors to business problems, as you see in this example. Then stakeholders need to determine which they want to collect additional information about. After selecting factors to fix, additional work is needed to see if the problem has lessened.

If you search “fishbone templates” online, you will find many to use.

What Is The Problem And What’s Contributing To It?

Business problems need to be stated very specifically. Otherwise, it’s quite difficult to develop a list of contributing factors. For example, I once talked with a VP who wanted all managerial staff to have “better business sense”. This could end up with a finance curriculum (talk about expensive!). So I asked what problems he was seeing that led him to identify managers not having adequate business sense and he gave me a list of four specific problems, including overspending in certain categories. Once we gathered some managers together and figured out the main reasons those specific business problems occurred, it looked like we had one training issue, a policy issue, and some lack of communication issues. Many were quite easy and inexpensive to fix. But it was also time to check those assumptions.

My favorite (and most productive) methods to gain information include asking questions and watching people who are affected by the problem to see when, how, and why they happen. You often need to get permission to do these things, but this kind of work is invaluable because you will often find additional contributing factors and be able to verify assumptions. There are a couple of rules I have found to be invaluable.

Rule 1. The specifics of what people tell you stay between you and them. You tell management up front that you’ll be reporting out major themes but not anything anyone specific says.

Rule 2. You are trustworthy and objective. If someone wants to dump on another department or person, you help them get to forward motion on the problem. “IT never helps us fix things that don’t work” becomes “We will see if it’s possible to determine how many duplicate addresses we have. If that’s not possible, we’ll see what is possible”.

I also like to help people understand if what they want is possible. Is q possible with the current tools in the current environment? Does anyone do q now? How do they do it? Under what circumstances? If not, what would be needed for q to occur? I’ve worked with people who simply say that they want q to occur but no one has ever been able to do it. And they’re unwilling to provide additional resources. That isn’t helpful and it doesn’t move solving business problems forward.

Of all the learning-related work I have done, this type of work has been near the top in value. I have worked with organizations that have a blame culture and this doesn’t work well there. (I’m not interested in helping people do that and I hope you aren’t either.) But most organizations really want to do good work and fix what doesn’t work. And that’s pretty great work.

References:

- How To Use The Fishbone Tool For Root Cause Analysis

- Shank, P. (2010). Performance Analysis workshop materials