Why We Need Learning And Development To Improve Expertise

Welcome to the beginning of 2017. I wanted to take a slight tangent this month and talk about something that has been on my mind a lot lately as I’ve talked to people at various conferences: Why we, as learning professionals, need to focus on how to improve expertise.

Learning and Development (L&D) may have multiple roles in organizations, but one of their most important is helping people do their jobs. But as I talk to L&Ders and see their work, it’s clear that many see their role as developing interactive content. And I’m disturbed by this thinking (I talked about why we need a larger focus here, too) because it’s problematic, I think.

While we may need to develop content, taking content (often of dubious quality) from others and putting into authoring tools is not the job organizations need from us. Look on any job site for content developer job tasks and pay. Is this the job you want to be doing? Just like most people type and edit their own work (unlike in the past where a secretary did it for you), content development is undergoing huge changes. Some will be automated. And experts in all fields will be able to easily build their own interactive content. (That is beginning to happen now. Search content marketing and you’ll see many articles on how this is taking off.)

Content is not what organizations need from good Learning and Development departments, even though some are still unaware of this. Most workers are already dealing with too much content. What people and organizations need from us is true Learning and Development expertise. Three of the most important aspects include:

- Analyzing and coming up with solutions to the entire range of performance problems, including the ones training cannot solve (see my previous article).

- Helping people gain, maintain, and upgrade skills (content doesn’t do this).

- Helping people adapt to huge changes to work, such as the need for continual learning (content may simply add more frustration).

In the rest of this article, I want to mainly discuss #2 because building content (alone) is not going to get us there. And if we don’t help our organizations get there, we are far less valuable and needed. I did qualitative research about a year ago, and talked to senior leaders about what they thought would happen if they no longer had a Learning and Development department. Almost all said the same thing: Nothing. Certainly, that’s harsh, but I believe it reflects the knowledge that we are not doing the right things to help our organizations prosper under current chaotic conditions.

Understanding Jobs

Think about what it takes to learn and stay up-to-date in a job. They are simply too complex to learn with content alone. To perform a job, you need to gain and then improve skills over time, relearn information as there’s simply too much to remember, find new sources of information to deal with current work issues, learn from others around you, and continue to learn as your job morphs over time.

Let’s use as an example a person who’d like to work in the medical industry. We’ll call her Suzanne, and she has a friend who is a medical billing specialist. Suzanne borrows her friend’s training books to learn about the work. Would Suzanne likely qualify for a medical coding/billing job after reading her friend’s books? Most people understand that reading books about a topic and training to do the job aren’t the same thing.

But getting trained and doing the work aren’t the same thing, either. Training cannot cover every single aspect of doing a job. Most training doesn’t use well-researched and effective techniques for remembering critical information so there will be a lot of information forgotten during that time that will need to be refreshed. Many formal training courses are slightly to a lot behind what is actually happening on the job. It’s extremely hard to keep complex job training up-to-date, as the training would need to be under continuous maintenance.

So, many people learn a great deal of their jobs, including the things that change and what to do in situations that are less clear-cut, on the job. When people come out of job training, most of the time they simply cannot do the job yet. They are still trainees at a novice level. They need much more practice and help.

As Williams and Rosenbaum explain, new trainees are typically not yet independently productive. Independently productive, per Williams and Rosenbaum, means that they can work at a specified level of proficiency without supervision. It is very critical to get trainees to independently productive because until they are at that point, they are making mistakes and taking up other folks’ time. They are expensive to have around!

Good training also helps people become better able to learn (Figure 1). That’s because knowing more facilitates more learning. More prior knowledge makes learning easier and faster. That’s one of the reasons why people with more expertise can learn faster and typically need different learning strategies than novice learners (this is part of the expertise reversal effect I discussed last month). And it’s another reason why we want to improve expertise levels of people working in the organization. They can do more and learn faster.

Figure 1. Learning gets easier and faster when you know and can do more

The essential point is this: Content alone doesn’t get trainees to be independently productive. When Learning and Development considers training as content and questions, they don’t understand the most critical outcomes needed from their work.

Improving Expertise

Most Learning and Development professionals understand intellectually that the purpose of training is to improve job skills (to increase organizational performance). To make this happen, one of our most critical goals is moving people to greater levels of job expertise. This typically doesn’t often happen with solitary event-based training courses.

For example, when training medical coders, the primary goal is improving the outcome of medical claims (not having claims returned, minimal rework, etc.). A person who sees their job as improving the outcome of medical claims and one who sees their job as delivering content on coding topics is going to do their jobs very differently. And only the former is likely to improve expertise of the medical coders s/he trains through ongoing training, practice, feedback, and other types of job help.

Here are some questions to consider to determine how well your Learning and Development group does at increasing expertise.

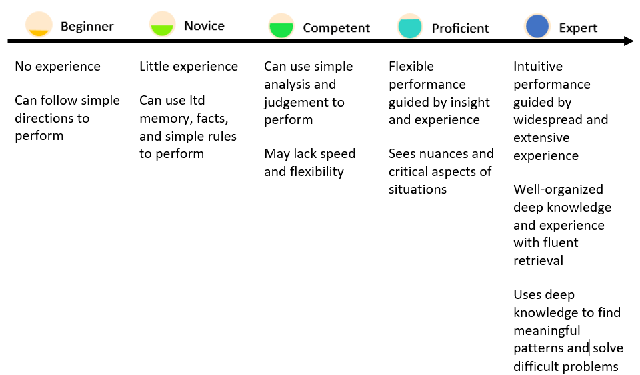

- At what level (Figure 2) does your organization consider people to be independently productive? How does your organization get people to that level?

- How does your organization help people get above that level, where people can truly solve business problems?

- What is the cost of having people working at too low of a level? What is your Learning and Development department doing to prevent or fix this problem?

Figure 2. Different levels of expertise and job performance (Source: Patti Shank, PhD, from Make it Learnable www.pattishank.com).

Ongoing work in a job, according to Ericsson, typically doesn’t improve expertise. Most competent people are on autopilot on the job, too busy doing their job to build skills that are more difficult to learn. They do not necessarily have access to the resources or people that could facilitate skill growth. (People also must want to increase expertise, as it’s difficult and requires more time and effort.)

Learning More

If you want to go beyond building content, where can you start? Start by learning how. How we best learn and gain job expertise. There are a lot of urban myths in our field (such as learning styles, digital natives, etc.) and they prevents us from doing the type of work that makes a real difference.

I have 3 specific reading recommendations for the new year.

- Urban Myths about Learning and Education by Pedro De Bruyckere, Paul A. Kirschner, and Casper D. Hulshof.

The book has a higher education focus but most of it is completely applicable to organizational learning. And it’s quite fun to read. - Peak: Secrets from the New Science of Expertise by Anders Ericsson and Robert Pool.

This one is harder to read and not as fun. If you cannot make it through, stay tuned and I’ll be discussing issues critical to organizations. - What Matters in Practice by Eduardo Salas, Scott I. Tannenbaum, Kurt Kraiger, and Kimberly Smith-Jentsch (here)

This research study describes the recent research that helps us get great outcomes from training. Especially look for the charts that show what matters most before, during, and after training.

Please feel free to comment and ask questions. I work on client projects so I am still connected to the real world of training. (And I oversaw a healthcare training department for many years.) But I do a much better job picking topics when I know your problems and issues. Let’s talk!

I certainly do know that changing people’s minds is not easy. But it’s what we must do to be successful.

References:

- Ericsson, K. A. (2016). Peak: Secrets from the new science of expertise. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

- Ericsson, K. A., Krampe, R. Th., & Tesch-Römer, C. (1993). The Role of Deliberate Practice in the Acquisition of Expert Performance. Psychological Review, 100(3), 363-406.

- De Bruyckere, P, Kirschner, P. A. & Hulshof, C.D. (2015). Urban myths about learning and education. Academic Press.

- Kalyuga, S. (2007). Expertise reversal effect and its implications for learner-tailored instruction. Educational Psychology Review 19. 509–539.

- Salas, E., Tannenbaum, S.I., Kraiger, K and Smith-Jentsch, K.A. (2012). The Science of Training and Development in Organizations: What Matters in Practice, Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 13 (2), pp. 74-101. 42.

- Shank, P. (March, 2016). Science of Learning 101: Job Performance and Expertise. ATD Science of Learning Blog.

- Sweller, J., Ayres, P. L., Kalyuga, S. & Chandler, P. A. (2003). The expertise reversal effect. Educational Psychologist, 38(1), 23-31.

- Williams, J. & Rosenbaum, S. (2004). Learning Paths. San Francisco: Wiley.