Learning In The Flow

True story. For several years, I commuted to work with public transportation. It took about 25 minutes and 10 stops to get to Center City, Philly. It was the same routine every single day; except, one day. I was working on a screenplay at that time and somehow this idea hit me while sitting on the train. I opened my laptop and started writing the scene. It was crystal clear what the character does, how the plot thickens, etc., I just had to write it down. I failed this scene many times before, which resulted in so many rewrites.

I always had this inner critic in my mind constantly blowing holes in my writing abilities. But this time it flowed. It took a couple of minutes to get it all out of my head and into the script. I looked up to check on the stops. I had missed mine. How was this possible? Did I just lose 20 minutes without realizing it? I had to get off and wait for the next train in the opposite direction.

Timeless State Of Mind

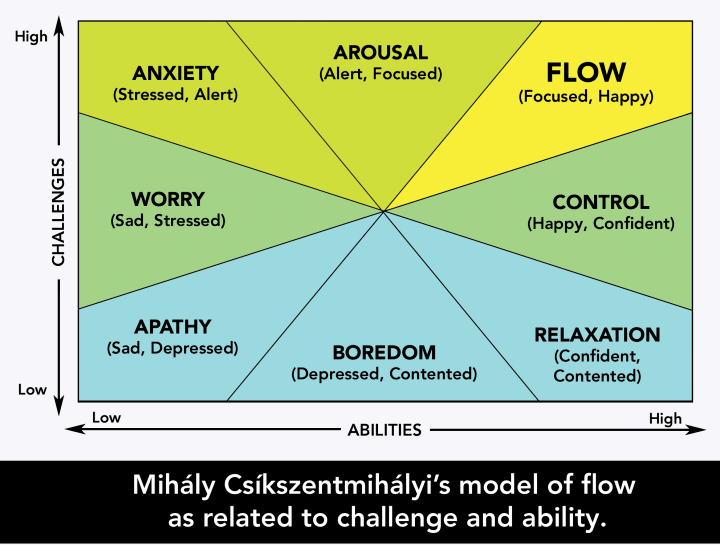

This "timeless" state of mind is when you're utterly focused without distractions on a challenge that is "right above your head," but you're absolutely confident that doing your best will conquer... this is what Mihály Csíkszentmihály's theory of flow is about.

One of the strongest indicators of deep flow is a distorted perception of time.

For some, the time would slow down, while for others hours would go by outside of their awareness. A brilliant study from the Kavli Institute discovered a network of brain cells that operates as a form of neural clock and explains how our subjective experience of time is tied to the ongoing flow of experience (Ratner, 2018).

In my previous article, we explored BJ Fogg's model for behavior change. This one looks at Csíkszentmihályi's theory of flow.

Keep Your Head In The Game!

One of the signature symptoms of the flow is the disappearance of your inner critic. That annoying voice you keep hearing when you're trying something new; that voice questioning your skills, strength, abilities; that voice telling you about the horrible things that could happen to you. Most of us listen to this critic from time to time, even professionals struggle with it. You have probably witnessed this in sports or music, where people performed "way above expectations," and when later interviewed, they just shrugged it off. When you're head is in the game, you can perform best.

I was watching an interview with Christen Press, one of the amazing players of the US Soccer World Champion team. She said her performance improved drastically when she started meditating and changed her style on the pitch: "If I simply stay in that moment on the pitch and read the game, I can do so much more..."

She explained how suddenly she was utterly focused on the moment, losing that inner critic that made her cry before. In those decisive moments, Christen knew exactly what to do. Almost like time just slowed down in front of her so she can do what she's best at—scoring.

Where To Experience The Flow?

Some of the most common conditions that you can experiment with are sports, arts, any creative activities, and of course, games. Well-designed games masterfully implement the flow: you have clear goals, your progress is rewarding, challenges arise with your ability to tackle them, etc. You feel like a world champion!

Why Aren't We Implementing The Flow At Work?

Now, obviously we all want world champion players on our team at work too. So, why aren't we implementing the flow on the job?

According to Csíkszentmihályi, there are two major barriers: lack of a clear goal and lack of immediate feedback. First of all, flow happens when you love doing what you're doing. That means you can't turn on the flow for a 9-5 f job that is just to make money. Second of all, workplace goals may not be as clear as game goals. In games (sports or otherwise), we have clear rules of engagement. Complex goals are broken down into tasks. You're always reminded that completing a task is not the end goal. It is a milestone toward the ultimate goal.

In well-designed games, feedback is perfectly timed to provide you a shot of dopamine as you conquer challenges. At work, it's rare that someone gives you feedback right at the moment you managed to do something fantastic. There's nothing more rewarding than "being caught" doing something really well. While good leaders acknowledge your achievements, they're often not as close to the moment itself as your peers. Peer recognition, therefore, is one of the key components of workplace motivation. Peer feedback from the team is much more likely to happen as you all are closer to the weeds of day-to-day tasks. That's one of the reasons why social learning is so critical in today's modern workplace learning ecosystem.

Research also shows that experiencing the flow as a team is stronger than experiencing it as an individual [1].

How Can We Attempt To Harvest All This When Designing Workplace Learning Experiences?

The biggest challenge I've seen with attempts of implementation of the flow is that perspective of the theory of flow is the individual's personal experience and not someone who designs these experiences. Just as we can't design learning, we can't design flow. We can, however, design the best conditions for it to happen.

There are 8 components required to reach the flow [2]:

- Complete concentration on the task

- Clarity of goals and reward in mind and immediate feedback

- Transformation of time (speeding up/slowing down)

- The experience is intrinsically rewarding

- Effortlessness and ease

- There is a balance between challenge and skills

- Actions and awareness are merged, losing self-conscious rumination

- There is a feeling of control over the task

Balance Between Challenge And Skills

As an "experience designer," you have more control over some of these factors. One of the most important elements is #6: balance between challenge and skills.

This point applies to any learning design as well. If the challenge is higher than the ability/skill, frustration may occur. If the challenge is lower than the ability/skill, boredom may occur. In theory, a good needs assessment can mitigate this problem for learning design. In practice, it is a much more complex challenge because the only way you can address everyone's balance is if your design is adaptive. A static course, no matter how well-designed, will never be effective for everyone. The concept of adaptive learning is that over time, the system learns about the individual's prior knowledge, skills, abilities, growth, etc., and adjusts the experience to balance challenges and skills.

At any point in time, depending on the relationship between the perceived challenges and skills, a person can experience one of these states [3]:

One of the misinterpretations of this graphic is that you just have to make sure the challenge is "right above your head" to reach the flow. If this were true, someone who has low abilities and facing similar low, yet a somewhat higher level of challenge, should achieve the flow. It's important to remember that the flow occurs when your perceived abilities are already high and matched with a slightly higher level of challenges.

Critics

This article would not be complete without mentioning the "flow of criticism" about the theory of flow. For one, many critics say that the theory of flow is merely a description of a state without much practical help on how to get there. In fact, you can't really force yourself into a flow. It just happens.

Conclusion

The theory of flow is about personal experiences. We do not design these experiences, we design the best conditions for these experiences to happen. The theory of flow has many barriers in the workplace. Without addressing those in workflow itself, it is unlikely that learning design can achieve the state of flow in itself. And so, you may not want to target the flow in your design right from the start. You may want to design an experience that over time enables the conditions for people to achieve the flow through continuously experiencing positive incentives.

Positive incentives stemming from learning, goal orientation, an experience of competence, interest, and involvement lead to subjects engaging in activities purely for the enjoyment of it (Rheinberg, & Engeser, 2018).

[1] Flow at Work: The Science of Engagement and Optimal Performance

[2] 8 Ways To Create Flow According to Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi

[3] Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1997). Finding flow: The psychology of engagement with everyday life. Basic Books.