My own Archive for Sexology has been offering a large sexological "open access" online library and "open access" online courses in several languages for more than ten years. Actually, I am the one who invented “open access” e-learning courses and for a long time, was their only - and very lonely - pioneer. In the meantime the electronic revolution has continued at its own exponential pace, while the academic sexology programs, such as they are, have remained standing still. However, others in other fields are beginning to catch up. Here is a recent example:Georgia Tech (the Georgia Institute of Technology in Atlanta, GA) charges its students on campus $45 000. for an M.A. in Computer Science. At the same time - and the first time - they now charge $7000. for the same M.A. online (Georgia Tech unveils first all-MOOC computer science degree).

5 Predictions For the Future of Higher Education

I think sooner or later this will happen:

- More and more students will get the degree online, and fewer and fewer students will get it on campus.

- Georgia Tech will make more money with its distant online students that it ever made with its students on campus.

- Once most or all of its courses have been fully developed and have become available online, Georgia Tech will be able to manage with fewer and fewer "overqualified" professors and will run its degree programs with cheaper "assistants" and "mentors". The most famous professors will get special contracts for the use of their names, for "updates", and for general supervision. The less renowned faculty members will become increasingly expendable, or at least will have to suffer demotions or salary and budget cuts. There will be less hiring of new, expensive faculty. Tenure will become a thing of the past.

- There will be an ever-widening gap between a university's money-making education and its money-devouring research. The latter will demand a percentage of the new income, and the former will resist that demand. The ensuing permanent budget wars will not be pretty. Eventually, research will lose out and will, even more than today, depend on outside funding. In the long run, the teaching and research functions of our universities will become totally separate and may even result in separate institutions with their own campuses, budgets, and administrations.

- One can easily figure out the rest. I myself predict this: As more and more universities around the world follow this trend, more and more distance students will flock to fewer and fewer "top addresses", i.e. to famous universities with proven records, the most successful programs, and the best cost-benefit balance. Less attractive universities will not be able to compete. Or they may try to compete with lower prices - a policy that could force them and other competitors to start a financial "race to the bottom" with everyone losing in the end. The "losers" will be "left behind" and gradually fall by the wayside, as the "winners" will be swamped with applicants and, with a relatively small senior faculty, will successfully handle hundreds of thousands of distance students.

It does not matter here whether the real Georgia Tech actually does follow the path outlined here or changes or even reverses its policies at some later time. I am citing it merely as an early example of a likely trend that many, if not most universities will have to follow in the future. Growing economic pressure alone will see to that. This pressure will also affect university libraries and other academic resources, and the accelerating "open access" movement will do the rest.These developments amount to a "writing on the wall" for our traditional, universities. So far, they have done little or nothing for the many millions of highly intelligent, highly motivated possible students in the developing world. Their potential lies fallow, because they cannot reach or cannot afford universities and libraries where they live. Now, for the first time in history, the internet has put the world's knowledge within their reach.Udacity, edX, and Coursera have developed new forms of education, indeed, of mass education. And they operate world-wide. They rely on cooperation between a number of institutions in different countries, and they encourage individual professors all around the world to go beyond the boundaries of their local institutions.

What will these institutions do in response?

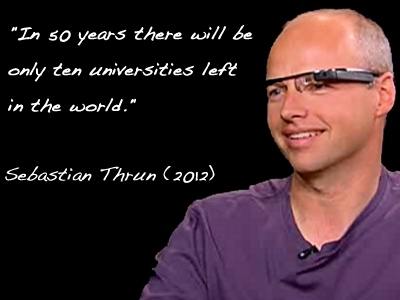

Will they promote or otherwise reward those of their faculty members who have gained new international fame and thus attracted tens of thousands of distance students? What will happen to their less prominent, less profitable colleagues? How many universities will give credit to their students for distance courses offered by professors in foreign countries? (Some major universities already do.) If a university does give credit for external courses, will it reduce its own personnel accordingly? Will it then be forced to give up some, many, or all of its own programs? How many universities will try to resist the increasing concentration of course offers in the hands of a few global operators? Would this kind of resistance have a realistic chance? Or could Sebastian Thrun be proven right, who predicted in 2012 that "in 50 years there will be only ten universities left in the world."