Instructional Videos And Effective Learning

The most powerful videos are those that allow learners to make an emotional connection with the topic. As you may have read in our previous article on cognitive theories of learning, the dual coding theory (Paivio, 2007) includes an emotional component as part of the rich variety of impressions that contribute to learning. There is evidence that learning of abstract concepts (which are not usually associated with concrete objects) is facilitated by association with emotional content (Kousta, Vigliocco, Vinson, Andrews, & Del Campo, 2011).

Before we delve into the applications of video for instruction, let’s take a look at the concept of the “Whole Learner”.

The Whole Learner: Cognition, Emotion, And Social Learning

Learning – and our response to learning interventions – is a complex process driven by a number of factors, including age, gender, socioeconomic status, etc. Learners who bring positive affective attitudes (interest in the topic and academic self-perception) tend to be more successful at learning (Çalişkan, 2014).

The ideal learning experience appeals to what Matteson (2014, p. 862) calls the “whole student,” addressing learners’ cognitive, emotional, and social characteristics. She reports the result of a study exploring the relationship of learners’ emotional and cognitive development to their competency in information literacy. She administered instruments to measure participants’ emotional intelligence, dispositional affect (how an individual perceives events emotionally), motivation, and information literacy.

Data analysis suggested that emotional intelligence (EI) was a significant predictor of information literacy scores: the more EI a person had, the higher his or her information literacy score. Based on her findings, Matteson recommended that instruction integrate emotional and cognitive awareness with course content.

Moving Toward Wholeness: A Comprehensive Model of Learning

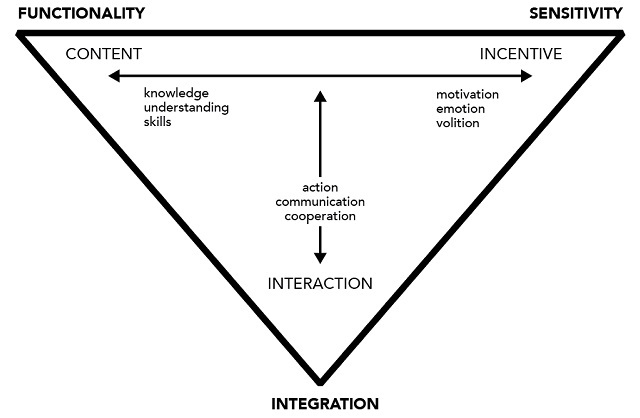

Illeris (2009, 2015) has taken what might be called a humanistic or holistic approach to theorizing the process of learning. As shown in Figure 1, he states that learning is an interaction among three dimensions: content, incentive, and interaction.

Figure 1. The 3 dimensions of learning. Adapted from Illeris (2009) / Credit: Obsidian Learning

The content includes knowledge, skills, beliefs, opinions, behavior, competencies, and so forth. The incentive is the mental energy (motivation, emotion, volition) that drives the learning process. Learning occurs through the learner’s interaction with the environment.

Genuine learning involves a subjective connection between the learner’s interests and motivations and the learning content, which always includes a cognitive, emotional, and social dimension. The dimensions are closely integrated: cognitive content is always subjectively influenced by the learner’s emotional and motivational drives, and emotional and motivational engagement is always influenced by the learning content.

Looking at the terms outside the triangle, we see that the goal of learning is personal wholeness. By engaging with content, the learner develops the ability to deal with the challenges of life, and so builds personal functionality. In the incentive dimension, the learner marshals motivation, emotion, and volition to achieve mental balance and personal sensitivity. Through such social activities as perception, communication, and participation, the learner achieves integration with communities and the larger society.

Instruction Videos: Applications

Videos are not only used to capture the intricate details of many subjects (as on Khanacademy.com, for example) but are often used to explain and simplify complex concepts, systems, or processes.

Because ideal learning videos are typically brief (from three to five minutes long), they are well-suited for mobile learning. In addition, instructors can use video in a “flipped” classroom setting, preparing their own video content for students to watch at home so that classroom time can be used for discussion and other activities (van der Meij & van der Meij, 2014; Giannakos, Konstantinos, & Nikos, 2015).

Another use of video is “video feedback” (VF), in which learners video themselves performing a task and then review the video to assess and improve their performance (Fukkink, Trienekens, & Kramer, 2011).

In a meta-analysis of research on using VR to improve the interaction skills of a broad group of professionals, Fukkink, Trienekens, and Kramer (2011) found that VF is effective at improving key communication skills, including verbal, non-verbal, and interactional skills.

Video And Psychomotor Skills

A question often posed in discussions of mobile learning is whether it is useful for teaching psychomotor skills. While cognitive skills can fairly easily be taught without the presence of an instructor, what about hands-on skills like device assembly or facility construction? Research indicates that video can be a key resource in teaching psychomotor skills at a distance.

Perspective: “How Do You Do It?” Or “How Would I Do It?”

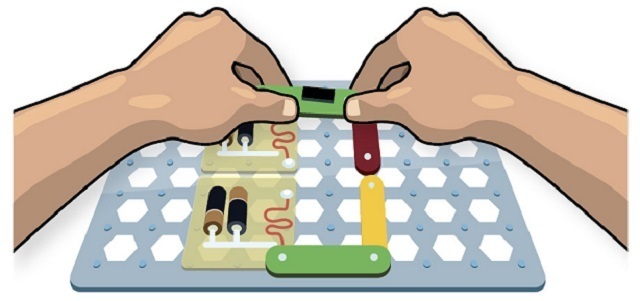

A quick look through instructional videos on YouTube reveals both third-person (a lecture-style, “this is how one does this” approach) and first-person (a more direct, “this is how you would do it”) modes of presentation. Research suggests learners do better when video is presented from a first-person perspective (Fiorella, van Gog, Hoogerheide, & Mayer, 2016). A first-person perspective allows learners to view a procedure from their own point of view:

Figure 2. First-person perspective. Adapted from Fiorella, van Gog, Hoogerheide, & Mayer (2016) / Credit: Obsidian Learning

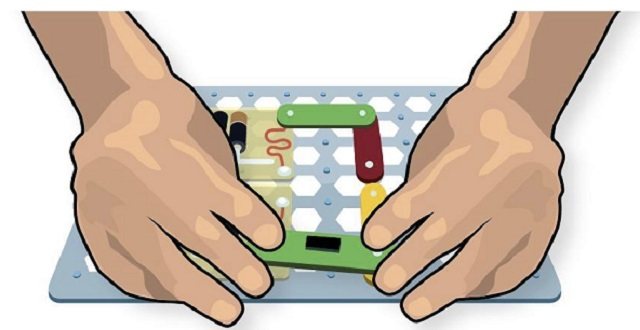

A third-person perspective shows another person doing a procedure:

Figure 3. Third-person perspective. Adapted from Fiorella, van Gog, Hoogerheide, & Mayer (2016) / Credit: Obsidian Learning

The third-person perspective results in extra cognitive load because the learner must mentally shift the action (for example, an object in the person’s right hand must be imagined in the learner’s left hand).

Observational Learning

Many courses require observation of proper technique, for example in teacher certification and other types of learning. Indeed, there is evidence that observation of others is a powerful way to learn (Fiorella, van Gog, Hoogerheide, & Mayer, 2016). This can readily be accomplished in instructor-led settings, but what about in an online environment? Grymes, Henley, Williams, and McBride (2016) describe the issues they faced when converting an early childhood education course to an online format. As part of their state’s licensing requirements, students are required to directly observe children in a classroom setting, but how could this be done in an online course? Their solution: curated video collections (on sites like YouTube or Vimeo) can be used to provide observational experiences to learners.

Health Education

In the domain of health education, Cooper and Higgins (2015) report the results of an experimental study of using video to teach clinical skills to physical rehabilitation students.

Three groups were compared: a control group that completed the normal classroom-based instruction, a group that did the same curriculum supplemented with short (1-2 minutes) videos, and a group that completed instruction supplemented with longer (10-18 minutes) videos. The videos were distributed online for learner use.

While data analysis did not reveal a significant improvement in course scores between the control and experimental groups, the authors speculate the videos provide value not measured in the study, including flexibility of use and just-in-time learning.

Construction Training

Donkor (2010) describes the results of a study that compared print-based and video-based materials to teach distance learners block-laying and concreting. Two groups of learners completed training using either print-based or video-based learning materials. Following training, learners were given a practical assessment requiring them to give a wall a 12 mm thick rendering and plastering on both faces and to finish each face with a wooden float. Learners also completed a multiple-choice assessment of theoretical knowledge of mortar and wall finishes.

For the practical assessment, the results of the video-based group were significantly higher than those of the print-based group. In the assessment of theoretical knowledge, there was no statistically significant difference between the two groups. Finally, the researcher compared the craftsmanship (defined as the learner’s display of a clean working environment, correct handling of tools and equipment, effective use of time, consciousness of safety, and judicious use of materials) of the two groups. As with the practical assessment, the craftsmanship scores of the video-based group were significantly higher than those of the print-based group.

The conclusion, therefore, is that video-based instructional materials are more effective than print-based instructional materials for hands-on skills acquisition and craftsmanship. For the teaching and learning of theory, however, video provides no added value. A follow-up study of learner satisfaction (Donkor, 2011) found a high level of user acceptance and satisfaction with video-based learning.

Police Training

In a brief case study, Eary (2008) describes a video system used to train Scottish police officers on how to respond to particular situations. Video of incidents (such as a tear gas canister explosion at a stadium) is combined with simulated radio and telephone messages. Learners work in teams, and each team sees video from only one perspective, just as they would in a real-life situation. Team members radio and telephone other teams to determine the appropriate response to the incident, again mimicking what would happen on the job. While the article contains no statistical data or analysis, it is an interesting example of how video and other media can be used to teach hands-on activities.

Tracking Informal Learning

In an earlier white paper, we described the importance (and the difficulty) of tracking informal learning (Victor & Werkenthin, 2016). Oliver and Moore (2016) present a solution in which students in an online course used Voicethread to provide instructor and peer support in the development of MakerSpace projects.

Voicethread allows users to capture their own activities (in this case, the design of simple scientific experiments) and thought processes and to interact with each other using text and media elements, including video. Using the tool, learners were able to solicit input and provide feedback on each other’s designs – something that is frequently done in “maker” projects but that is difficult in an asynchronous online setting. The result for the learners was a “natural style of documentation” of their own (and others’) informal learning processes.

Industrial Health And Safety

The term “interactive” might not be precisely defined in the literature. For Zhang, Zhou, Briggs, and Nunamaker (2006), interactivity in video refers to tools that allow learners to search for topics and navigate within a video, rather than simply watching a video from beginning to end. Their research revealed improved learner performance and satisfaction with interactive videos.

On the other hand, Cherret, Wills, Price, Maynard, and Dror (2009) describe the use of interactive videos in which learners take an active role in engaging with and participating in activities being taught. They describe the results of a study in which learners heard a 45-minute lecture on risk assessment in construction management. Following the lecture, learners accessed an online interactive video and completed a risk assessment task. The video was developed in Adobe Flash and required the following tasks:

- Learners identified hazards by clicking on them in the video.

- The video then showed learners all of the hazards, together with text and images explaining why the situations were hazardous and how to avoid them.

- Finally, the video played again in its entirety, with the hazards being identified and described without learner action.

In response to a Likert instrument using a 1-5 scale (1 = strongly agree, 5 = strongly disagree), 65% of learners strongly agreed that the lecture/video combination was effective for new students, and 75% stated that the interactive video had enhanced their learning. The authors suggest that this blended approach could be used for both “hard skills” (such as emergency evacuation procedures) and “soft skills” (such as decision-making, communication, and leadership).

If you want to learn more about using video for instruction, download the eBook Transforming Learning: Using Video For Cognitive, Emotional, And Social Engagement.

Related articles:

1. 3 Cognitive Theories For Transforming Learning

2. 5 Stages Of Instructional Video Development Process – Feat. A Case Study

3. 6 Top Tips To Design Effective Instructional Videos

4. eBook – Transforming Learning: Using Video For Cognitive, Emotional, And Social Engagement