A Story About Learning Anything

“And then you start thinking like an octopus.”

I make a living helping people create training courses, and as I watched the film, I couldn’t help thinking, how did Craig learn that? I was fascinated by his discovery of the octopus and then his deliberate process for teaching himself about her world. I rewatched the film multiple times. I took notes. I created a framework for understanding his learning process. I started thinking like an octopus.

This is the story of how Craig learned that.

To formulate my framework I leaned heavily on ideas from Peak, the book by Anders Ericsson and Robert Pool. I created this rubric of questions to guide my understanding of his mastery.

Click any of the questions to jump straight to that section.

- What is the nature of his ability?

- What training made it possible?

- What got him interested in the first place?

- When did he make a commitment to master it and why?

- Did he focus more on why or how?

- What were the leaps of understanding he went through?

- When did he enlist the help of a coach or mentor?

- What role did getting out of his comfort zone play?

- What experiments did he run?

- What did his practice regime look like?

- How did his belief in his own mastery affect his motivation?

- Was there ever a time he felt like quitting? How did he get through that?

- What role did his friends and family play?

- How did he measure improvement?

- What’s next? What new paths does he want to forge?

1. What Is The Nature Of His Ability?

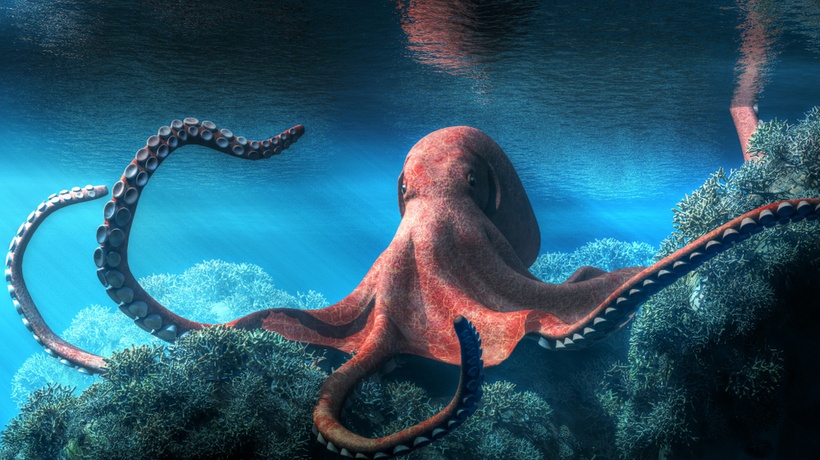

Craig Foster taught himself how to track animals underwater.

Let that sink in for a bit.

These are creatures that have spent millions of years learning how not to be found. Creatures that live in tiny spaces under rocks or buried in the sand.

He had to learn how to find their tracks, incredibly difficult markings to discern on the constantly shifting ocean floor—What’s the difference between octopus tracks, sea urchin tracks, and fish tracks? He had to learn about predation marks, egg casings, algae, and the role of kelp.

He did this by visiting an octopus that captured his imagination every day for a year. He learned to pay attention and started to notice extraordinary things about octopuses. They can look spiky or smooth. They can grow horns. They can match color, pattern, and texture with their skin. They can mimic rocks and flowing kelp to avoid prey. They can walk on two legs!

He understood how the entire ecosystem of the kelp forest worked in balance. “The forest brain,” as he called it. Through his journey of discovery, he learned about himself too. He learned how to be vulnerable. How to love an animal. And as he says in the film, he learned that “you’re part of this place, not a visitor.”

2. What Training Made It Possible?

3 things stood out:

- Consistency

He went every day to the same small patch of the kelp forest. (More on why this was important later.) - Preparation

Everything about his kit had to be perfect: no fiddling; it had to be instinctive to film or use his tools to allow him to blend into the environment. He also pored over research papers and his film at night, preparing for his dive the next morning. - Curiosity

At one point he says about the octopus, “she ignited my curiosity in a way that I had not experienced before.” I believe this is what motivated him to keep going back every day.

It’s time to zoom out now.

Slowly we’ll zoom back in over the remaining questions to see how he learned to track animals underwater.

3. What Got Him Interested In The First Place?

Craig grew up on the tip of Africa in an area known as the Cape of Storms in a wooden bungalow pretty much in the Indian Ocean. Waves would crash into their house during bigger storms, filling the young boy with the feeling of adventure.

He would go diving in the kelp forest. “My childhood memories are completely dominated by the rocky shore, the intertidal, and the kelp forest.”

In Ericsson’s research on experts, he found that initial curiosity-driven motivation needs to be supplemented. He identifies the “satisfaction of having developed a certain skill” as a component of motivation and you can’t help but feel that Craig got really good at ocean diving and enjoyed it more as a result.

Finally, he worked in the Central Kalahari later in life, making a documentary about some of the best trackers in the world—the hunter-gatherer tribe known as the San. He was captivated by their ability to track animals in the desert and wanted to live inside that world, connecting to nature completely.

These two formative experiences set him up perfectly to become a master at tracking animals underwater.

4. When Did He Make A Commitment To Master It And Why?

There is often a turning point for those that have mastered a skill. A point at which they commit fully to the deliberate practice required to attain mastery. For Craig, that seems to be the burn out he experienced after working for 18 years as a filmmaker and the exhaustion and disinterest that followed. He talks about how his mental state affected his relationship with his wife and son.

He needed to make a radical change.

This led him to spend every day bare-skin, no-tank diving in the freezing Atlantic, moving through 3-dimensional underwater kelp forests.

And then he met her.

5. Did He Focus More On Why Or How?

He talks about being obsessed with her and not being able to wait to go back into the water. This suggests he was driven by a deep "why" to understand this fascinating and elusive liquid creature. "Sometimes you just get this feeling and you know, there is something to this creature that’s very unusual. There’s something to learn here."

The "how" (navigating the kelp forest and tracking animals) became his means of being with her.

6. What Were The Leaps Of Understanding He Went Through?

The first leap came after a few days of diving. He found a small patch of kelp forest, protected from the swells. Here his eyes were opened to what was around him. The biggest leap was the discovery of the octopus. It wasn’t just an ordinary discovery though. He found this strange creature covered with shells, rolling along the ocean floor. He realized it was an octopus, cunningly avoiding the pajama sharks in the vicinity. This fascinated him, firing off his curiosity to learn more. “And I had this crazy idea, what happens if I went every day?”

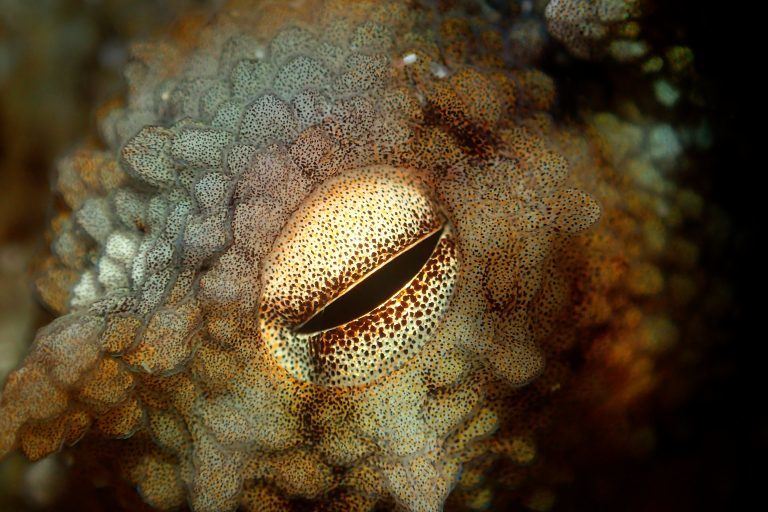

After 4 weeks of visiting her, her fear subsided tremendously, she became interested and curious, but still took no chances. Eventually, he put out his hand, and she reached out with her tentacles and touched him. This moment shook him to his core. “Something happens when that animal makes contact”

Another powerful leap was when she came out of her den. That was when he knew she trusted him. He started to realize she was getting something out of their relationship too—it was stimulating her huge intelligence.

He goes on to observe her outwitting prey (more on that later). Another day he sees her playing with a shoal of fish after which she cuddled with him. He was witnessing highly developed social instincts from an extremely reclusive animal.

These leaps of understanding gave him the source of motivation he needed to get out of his comfort zone and engage in the deliberate practice necessary to learn how to track her.

7. When Did He Enlist The Help Of A Coach Or Mentor?

Ericsson says in Peak that even “the most motivated and intelligent student will advance more quickly under the tutelage of someone who knows the best order in which to learn things, who understands and can demonstrate the proper way to perform various skills, who can provide useful feedback, and who can devise practice activities designed to overcome particular weaknesses.”

Craig was no different.

The San master trackers he filmed demonstrated the skills required to track an animal in the wild. And of course, his Octopus Teacher gave him all the feedback he needed to learn more about her world.

8. What Role Did Getting Out Of His Comfort Zone Play?

Ericsson explains another lesson from his research: "The fundamental truth about any sort of practice: If you never push yourself beyond your comfort zone, you will never improve." Essentially, learning is trying to do something you haven’t done before, until you can. When you reach a barrier, you find a way around it. For Craig, getting out of his comfort zone meant two things: diving bare-skinned in the freezing Atlantic and not using a tank.

The Atlantic Ocean around the Cape Peninsula can drop as low as 8°C (46°F). Ocean swells toss anything caught in it from side to side like an industrial washing machine. “In the beginning, it’s a hard thing to get in the water. It’s one of the wildest, most scary places to swim on the planet.”

But after about 10-15 minutes of enduring the cold, everything starts to feel ok. “The cold upgrades the brain because you’re getting this flood of chemicals every time you immerse in that cold water. Your whole body comes alive.”

For Craig, it got easier and easier until after about a year he “started to crave the cold.”

As for relying on his own breath, he found having a scuba tank in the thick kelp forest to be sub-optimal. “You naturally get more relaxed in the water and are able to hold your breath for longer.” These two victories over discomfort allowed him to take another step towards mastery. “If you really want to get close to an environment like this, it helps to have no barrier to that environment.”

9. What Experiments Did He Run?

“We can only form effective mental representations when we try to reproduce what the expert performer can do, fail, figure out why we failed, try again, and repeat over and over again. Successful mental representations are inextricably tied to actions. ” – Anders Ericsson

Craig stacked a series of actions over time to slowly build his skill at tracking animals underwater. Here is a quick summary:

- When he first found her, he left a camera as he knew she was affected by his presence. This allowed him to observe her by watching the footage.

- He started to document the environment around her by taking photographs of landmarks and sketching their relationship on a map.

- He made mistakes too:

-

- One day she was following him and he dropped one of his lenses giving her a huge fright.

- Another day he approached her too fast and startled her out of her den. He feared he had lost her.

- On day 104 he started going out at night and found her in the shallow water hunting.

- On day 271 he found her hunting a crab and lobster. He noticed her develop an elaborate strategy for hunting by trial and error, even using him in her approach. For example, she learned and remembered details like where to drill into the shells of mollusks to inject her muscle relaxant precisely into the abductor muscle.

- On day 304 he witnessed her climb onto a rock, leaving the water to escape a pajama shark. Not able to sustain being out of the water she had to return to face the shark. That’s when he saw her wrap herself in the shells in one quick movement, creating a barrier around her which the shark is unable to penetrate. At one point she gets into the least dangerous place—on the shark’s back! She escapes, completely outwitting the shark.

This series of leaps make him realize how intelligent the octopus is and feed his hunger to learn more, requiring him to get better and better at tracking her.

10. What Did His Practice Regime Look Like?

He had a clear routine. He visited her every day in the same spot. “That’s when you see the subtle differences, and that’s when you get to know the wild.” He dreamed about her at night. He thought like an octopus, which he describes as “incredibly taxing.” This speaks to the dedication it requires to immerse yourself in mastery.

In the water, he captured images of tracks, predation marks, and egg casings. At home he pinned them on his wall, categorizing them. He mapped out the terrain with places like "Sandy Lagoon" and "Father of Dragons Crack." He read scientific papers at night to interpret what he was seeing. He went back every day with a clear idea of what he wanted to observe or test.

In short, his practice regime was all-consuming and very deliberate.

11. How Did His Belief In His Own Mastery Affect His Motivation?

A series of breakthroughs fired his motivation, like a detective picking up small clues in a challenging case. At first, these were tiny breakthroughs, but just enough to keep him going:

- Finding shells of animals she had killed

- Discerning diggings in the sand

- Noticing changes in algae

- Realizing she was very close

Until one day he finds her, after weeks of looking.

He felt her trust. She crawled onto his hand. He had to go up to breathe. She clung on. She didn’t leave his hand even when his head broke the surface. “The boundaries between her and I seemed to dissolve.”

His mastery of underwater tracking led him to a friend, a friend he was going to continue to learn from. That gave him endless motivation to keep going.

12. Was There Ever A Time He Felt Like Quitting? How Did He Get Through That?

There is one point in the film where pajama sharks clamp down on her. In a violent death roll, they tear off and leave with a severed arm. She is alive but very weak.

Craig wrestled with whether he should interfere, but realized it was not his place to meddle with the course of nature. For days he felt like he was responsible, that she was out there because of him. This caused him to reckon with his own mortality. The next day, overcome with emotion, he tried to feed her a little, but it didn’t help. He checked back every day, grappling with the feeling that it might be the last time he’d see her. Until one day he noticed that her arm was growing back. He realized she could get past the difficulties she had and it made him realize he could do the same too.

This experience improved his relationship with his son and his wife, as he came to terms with his own vulnerability. Their role went on to play a big part in his motivation.

13. What Role Did His Friends And Family Play?

Craig’s son started showing an interest and he called it “one of the most exciting things” in his life to share his knowledge of the kelp forest with him. He talks about how his son developed “a strong sense of himself, an incredible confidence, but the most important thing, a gentleness, and that’s the thing that thousands of hours in nature can teach a child.” As a father myself, I can feel the deep well of motivation and pride that must’ve given him.

Craig’s wife isn’t featured in the film, but she helped make it and writes about nature and conservation. She understood what he was doing and no doubt played a huge role in supporting him while he did it. Ericsson observed the important role support from friends and family played in his studies of experts and Craig definitely benefited from that too.

14. How Did He Measure Improvement?

The road to mastery is filled with obstacles, as we’ve seen. Without some way to measure your progress, motivation quickly wanes. Luckily Craig had a few good ways to do this. The first and biggest sign of progress was finding her. Two more measures of success stand out in the film. One is his ability to notice patterns. This is a sign of strong mental representations. The second is related, and it’s his ability to predict what might happen. He is able to take his mental representations and extrapolate what his octopus teacher might do in a given movement. This must’ve been deeply satisfying.

Finally, at the end of the film, and the end of her short life, Craig is there to witness her mating and death as she gives all her energy and body to her eggs. He watches her die slowly, as she times her passing with the hatching of her eggs.

Months later he is diving with his son when they find a tiny octopus.

Another sign of progress, both in their mastery of the kelp forest and in the circle of life.

15. What’s Next? What New Paths Does He Want To Forge?

Craig continues to explore and learn about the kelp forest and all its inhabitants, big and small. But he’s not alone anymore.

He co-founded the Sea Change Project, a growing community of divers dedicated to the lifelong protection of the kelp forest. If Craig’s story moves you, you can help protect the Great African Seaforest by donating through their website.

A special thank you to Gwen Sparks of the Sea Change Project for supplying the images for this post.